False Assumptions and Cognitive Biases

To keep life manageable, and so we don’t run out of steam before we leave the house in the morning, we develop a series of mental shortcuts, aka habits. Habits aren’t only things like brushing our teeth and locking the front door, but also include our route to work and whether we take the elevator or stairs. Without these mental shortcuts, we would be exhausted by the number of decisions we would need to make before we reach our desks. Unfortunately, these same mental shortcuts also cause us to miss key questions, misjudge, and misunderstand risk.

Gambler’s Fallacy – we tend to put weight on past events, thinking they’re likely to affect future events, even when they’re independent. Example: flip a coin 9 times. If each result is heads, we tend to assume that it’s very likely the next one will be tails. Yet it’s still 50%.

Observational Selection – right after we buy a new car, we notice that there are more cars of the same model on the road. Yet the number of cars on the road hasn’t changed – what has changed is what we notice.

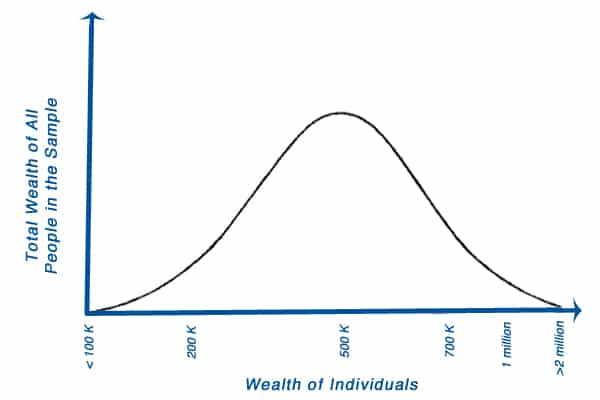

In the business world we tend to assume that a bell curve or normal distribution applies anytime a number is quoted to us (numbers are often quoted as an average). For example, if I asked you to show me a model of the wealth of 10,000 randomly selected people it would probably end up being a graph like this:

2 standard deviations – 95% confidence interval

3 standard deviations – 99.7% confidence interval

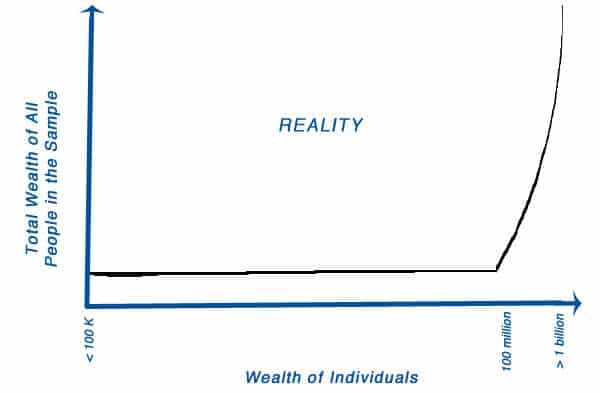

Yet there is a very good chance that your sample included a few people with a net worth of over $50 million and even one of $500 million. In which case, our bell curve isn’t a good model for what we actually found. Even better, if I ask you to ensure that your graph includes the wealth of Bill Gates, now the graph likely looks more like this:

Because we tend to assume that normal distribution applies to most numbers we see, we fail to correctly estimate the likelihood of extreme events.

Nassim Taleb (“Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder”) calls these extreme events “Black Swan events”. Events that normal distributions underpredict by a multiple of thousands. For example, assume that stock price movements on the S&P 500 index fit a normal distribution, and that events that fall 5th standard deviations from the mean have a 1 in 3.5 million chance of happening. Yet in 1987, the S&P index had 3 such days, and over 50 since it was first created. The S&P 500 was founded nearly 60 years or <22,000 days ago (this includes weekends and holidays), so if a bell curve applied, we would expect 0 or 1 extreme events thus far.

Our attempt to use numbers as our primary way to measure and manage risk misrepresents the real risks because our models give us false assurance. Our models do a good job predicting the normal, everyday events, so we believe them. However, we significantly underrepresent drastic events, making them seem almost impossible even though they’re not.

Numbers are useful, but give us only a small piece of the picture.

See also: Linear Thinking in a Nonlinear World by Bart de Langhe, Stefano Puntoni, Richard Larrick

[…] False Assumptions and Cognitive Biases Written by: Mark Levison […]