The “Spotify Model” probably isn’t a model and definitely isn’t what is currently practiced at Spotify today. (Some suggest it never was.) The below image was made famous in a video by Henrik Kniberg, where he explains how work was organized into Squads, Tribes, and Guilds. Many people see the structure and try to mimic it in their organization. Worse, many attempt to get the supposed benefit by renaming existing organizational structures with the same labels. As a result, most attempts at the Spotify Model are in fact Cargo Cult.

Structure isn’t the most important. Culture will eat any structure. (Hint: that’s why renaming your Teams as “Squads” and calling Departmental Managers “Chapter Leads” didn’t help.) That said, if I don’t summarize those labels, you will look elsewhere anyway, so here we go:

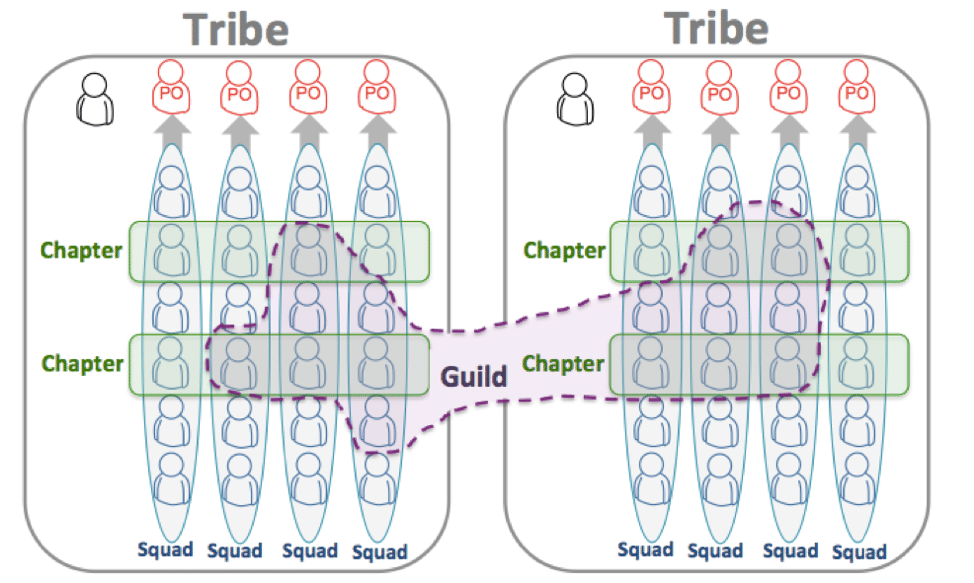

- Squad: effectively a Scrum team with a new name. When the original paper was published, each squad owned a small chunk of the UI or behaviour of the system. They own this slice of the product and can run experiments without depending on other teams. People who are familiar with LeSS will notice that squads are feature teams.

- Tribe: a collection of squads that work in a related area. They’re designed to have collaboration across squads with few dependencies, on other tribes. Tribes are capped at 100 people to minimize “restrictive rules, bureaucracy, politics, extra layers of management, and other waste”.

- Chapter: people of a single skill area inside one tribe, e.g. testers or developers who work with a certain technology. Chapters meet regularly to discuss problems and share learnings in their field.

- Guild: a larger community of interest. Guilds usually include the chapters, however anyone who is interested in a topic can join a guild. When the original paper was written, they had guilds for Web Technology and Agile Coaches Guild.

Structurally, this is a perfectly sound way of organizing teams. The pitfall is that it changes labels without the cultural and mindset change to go with it. And education alone won’t make that change.

Is this just another matrix model, the sort of thing that Agile coaches have been undoing for years? Yes, it is, but it’s a different kind of matrix. In other matrix models, the horizontal relationship is the primary one. E.g. A developer reports to a dev manager; a tester to test manager, etc. Affiliation with the team(s) they work with is more loose. Spotify reversed this. The primary relationship is as a member of a stable, cross-functional team. The chapter lead (not a great choice of name) is a coach, focusing on skill and technical excellence. In theory, this is great. In practice, this is the first place many organizations make a mistake. Your chapter leads aren’t former managers who got a new job title.

There are a myriad of other mistakes people make from reading a whitepaper and watching a video. The list would be longer than the original paper. So popular is this problem, it’s even got its own meme:

Instead, focus on the things that Spotify had going underneath the hood:

- Delivering Value – all improvements to the system should be tested by asking: Does this improvement/experiment, help us deliver value?

- Delivering Product Value – requires running experiments and seeing what works for real end users.

- Autonomy over Command and Control – without autonomy there is no learning, improvement, innovation or ability to adapt to changing circumstance.

- Alignment – instead of telling people what to do for both product features and product architecture, focus on getting teams to align to a common product goal. Consider having multiple teams working from a common Product Goal.

- Cross-Functional Product Oriented Teams (aka Feature Teams) – rather than building teams according to their functional layer (e.g. Database, Business Logic, UI).

- Engineering Culture that focuses on building Quality and Simplicity – build a Continuous Delivery pipeline that allows teams to deliver value independently of one another. Versus a pipeline that requires waiting for the DevOps team to deploy for them. Hint: in many organizations, DevOps is a team downstream from the feature team, who deploy the application. This is a well-known anti pattern.

- Psychological Safety – the original paper called this “experiment friendly”. The key element of experiment friendly is creating an environment where we can acknowledge taking risks and learning from the process. The fancy name for that is “psychological safety”.

- Continuous Improvement as a feature of the system – teams are never done improving. We need to create cultures that promote this mindset.

- Morale – originally referred to as happiness, this is the willingness and the persistence of team members to work towards a common good.

- Improving the Flow of Work through the system – tools include Limit Work In Progress (aka WIP), Cross-Skilling, and Eliminating Bottlenecks. You can measure the success of this with both Cycle Time and Lead Time.

Agile Pain Relief is committed to helping new Agile professionals who want to learn the language of Scrum and become confident knowing what’s what, so you can focus on helping teams become the most effective they can be. Join us for our Certified ScrumMaster training courses and discover how true Agility actually works.

[…] a brief aside, this is a great post about why “The Spotify model” isn’t quite what most founders think it […]