Agile Bonuses - The Damage They Do

A design pattern is a description of a solution to a recurring problem. It outlines the elements that are necessary to solve the challenge without prompting the reader to address the issue in a specific way. Unfortunately, we also regularly see recurring patterns of ineffective behaviour. These are called Anti-Patterns. The following explores the common anti-pattern of a performance bonus. Micromanagement.

A few months ago a friend asked me about setting up a bonus scheme at his work. From working with Scrum and Kanban teams, I know that bonuses are counter-productive anywhere team members are doing knowledge work and their work is interdependent. The same might apply in other areas too, but I know this to be true in the context of software development in particular, because of my experience and study.

What kind of bonuses are we talking about here? Not Christmas bonuses, profit sharing, employee stock ownership plans or stock options (although, if not used carefully, even those have risks). We will focus on only performance bonuses for this article, which is what my friend was discussing.

“A performance-based bonus is an extra compensation granted to an employee as a reward for reaching pre-established goals and benchmarks.”1

In software development, individual performance bonuses are often geared to something like personal velocity if you’re a developer, or number of defects found if you’re a tester. For team bonus, maybe the target would be set as “greater than 75% of committed stories are completed in most Sprints”. We’ll use the developer example in our illustrations, but others would have similar effects.

After a short conversation with my friend, we managed to identify a number of ways that bonuses would be a bad idea and I offered to assemble research for him as ammunition to convince his boss. And what I found in the research was curious. It showed that researchers have a very narrow focus when studying bonuses. With a couple of exceptions, they assumed that the people designing the incentive had chosen a good target.

Of course, from our experience in the agile world, we know that most targets are either outright dangerous (e.g. velocity as a measure of throughput) or far enough from the truth that focusing on them may cause harm (e.g. defects as a proxy for quality). Researchers don’t tend to look very far forward when they assume that bonuses will have a positive effect and they end up measuring the wrong things. If they instead ignore any assumed target, and follow cause and effect to the unbiased end results, they would see that.

Other challenges with common research:

- Many of the tasks being measured are too simple. For example, in online game play, the task is designed to measure collaboration and competition. Unfortunately, the limited complexity of game play doesn’t simulate product development work well.

- Many studies are run over a short period of time - hours or days - so would not show the long-term effects of most bonus schemes.

- Since the research is typically based on short time periods, it rarely examines the effects of bonuses on morale or intrinsic motivation. Adding more effective motivation tools to this article might double its length.

To see what goes wrong with bonuses, we’re going to draw on a few tools.

- Goodhart’s Law - “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”

- Motivational Models - specifically ARC

- Systems Thinking - many of the problems created by bonuses come from a lack of consideration to knock effects. I.E. If we do X, what other effects will that have downstream? What effects will it have in a few months?

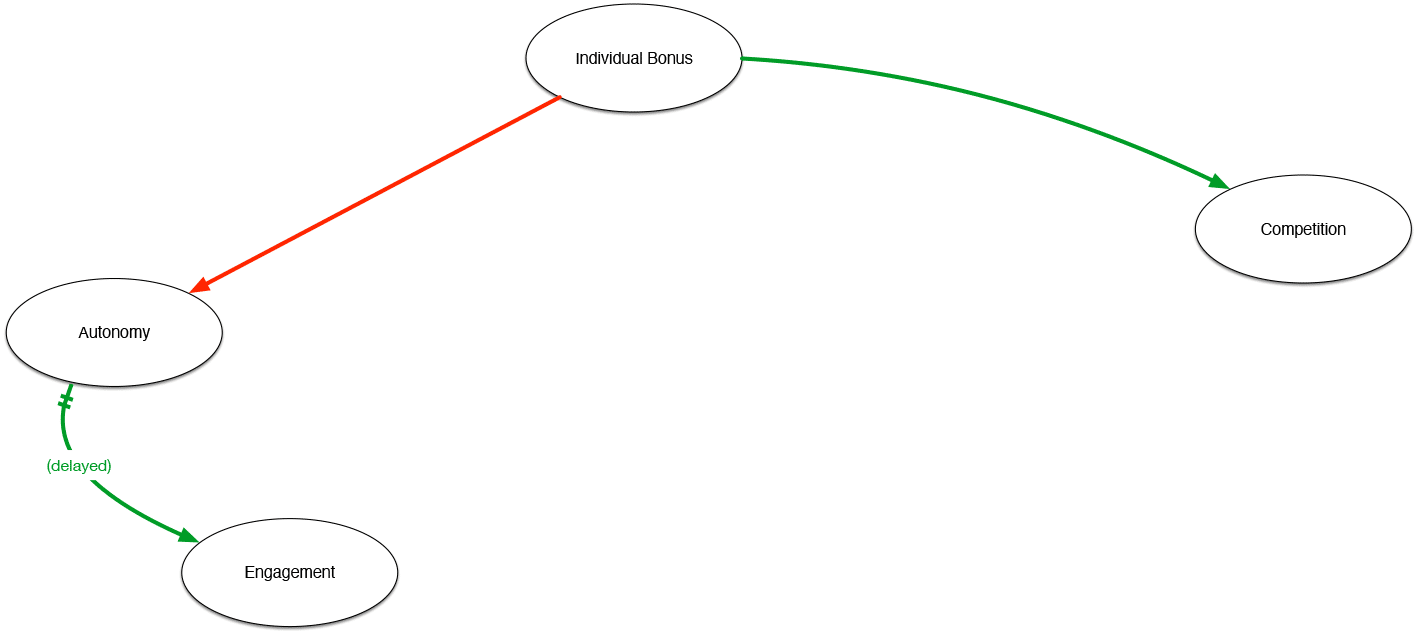

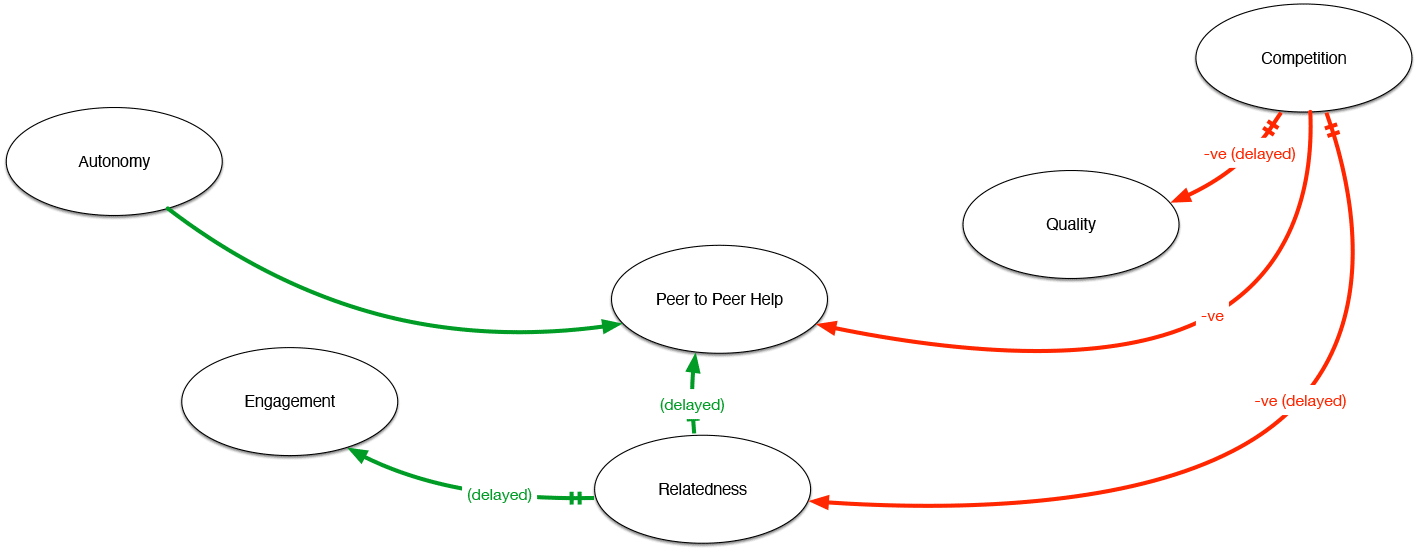

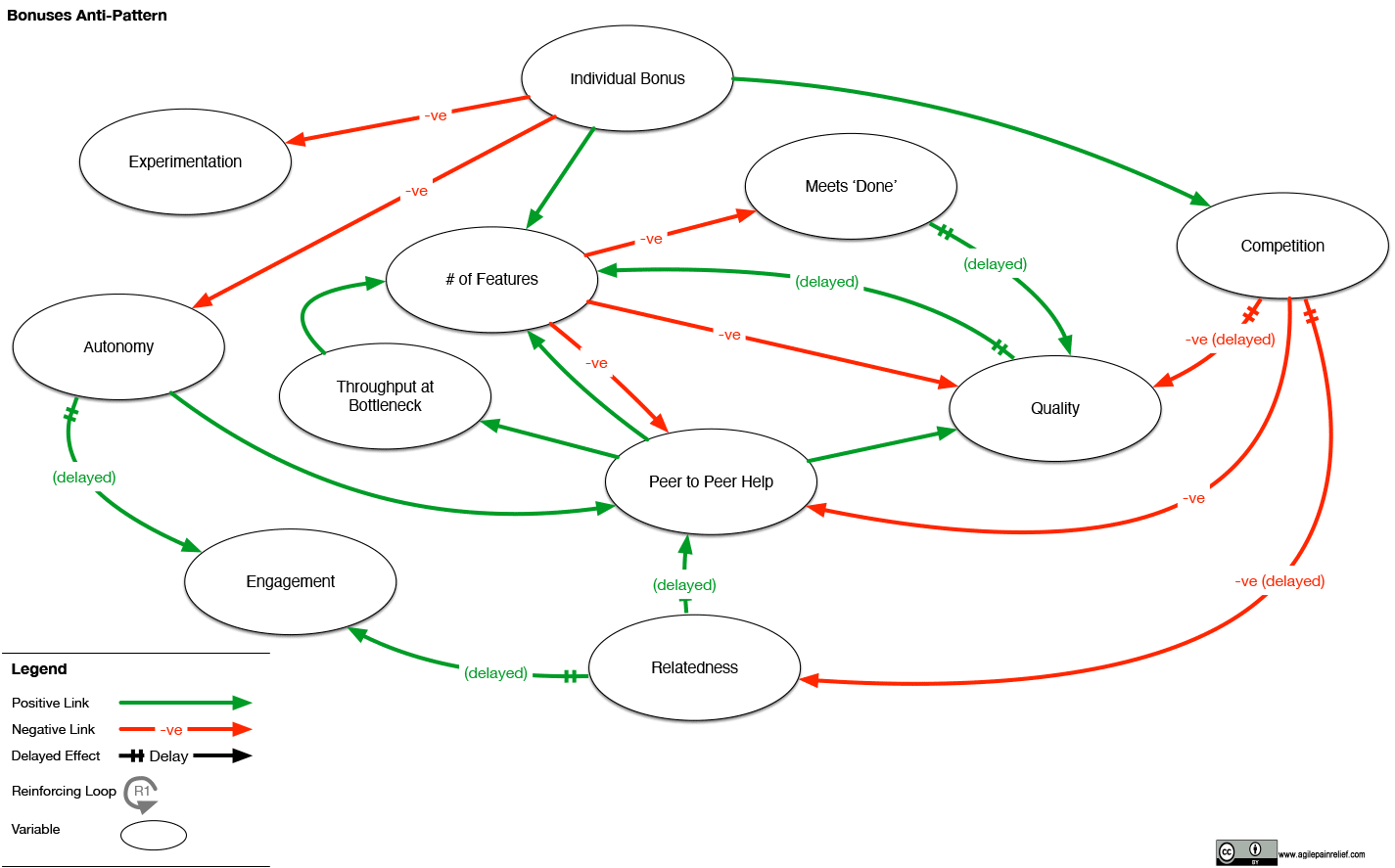

And to visually illustrate cause and effect, we’ll use Causal Loop diagrams to show positive and negative links. Remember, “positive” and “negative” shouldn’t be read as good or bad, but simply as increasing or decreasing.

Individual Bonuses

Here’s a hint right out of the gate if you’re new to Agile: you never want to measure anything for one person.

Individual Bonus (-ve)-> Autonomy - Chasing a bonus lessens the opportunities we have to make decisions to better the team because meeting the bonus requirements becomes the higher priority. This reduces (i.e. negative link) a team member’s Autonomy (see ARC and SCARF models).

Autonomy (delayed ->) Engagement - When we have Autonomy —control over our own choices— we have a greater sense of Engagement. But the bonus has reduced Autonomy, causing an opposite effect. It turns out, Autonomy is a core driver for Engagement at work.

Individual Bonus -> Competition - An individual bonus also increases (i.e. positive link) Competition between team members. It automatically means you should put your own needs ahead of the team’s needs, to maximize your bonus payout. Since others are doing the same thing, your cooperative Scrum team starts to have competition between members.

Competition is a fun one because it sparks a lot of effects of its own…

Competition (-ve)-> Peer to Peer Help - You will still help others, but only after your own work is done and mostly on a quid-pro-quo basis. This isn’t healthy collaboration and reduces the amount of Peer to Peer Help that happens.

Competition (Delayed -ve)-> Quality - As Competition increases and communication declines, more errors creep in. There is reduced cooperation between individual developers and, much worse, reduced cooperation between developers and testers. Have you ever been in a bug triage meeting where one party claims they’ve found a bug and another person claims it works as designed? This happens enough even without incentives getting in the way, and bonuses just make this much worse. Reduced Quality is a delayed effect; it will take a lot longer to show up.

Competition (Delayed -ve)-> Relatedness - We have a need to care about, and feel cared for by, others. As the feeling of Competition increases even a little bit, that harms our ability to Relate to others.

Relatedness -> Peer to Peer Help - As we get to know our teammates better and learn to care about them, our willingness to provide support increases. Unfortunately, Competition harms Relatedness and, therefore, further undermines the Peer to Peer collaboration required for Agile to be effective.

Relatedness (Delayed)-> Engagement - When we feel we’re part of something bigger than ourselves, our Engagement goes up and then we become more productive. The competitive environment which harms Relatedness, also creates dis-engagement.2

Autonomy -> Peer to Peer Help - When we have freedom to make choices, it is easier to collaborate because you don’t feel as much pressure inside yourself to get your own work done first. Instead, you can help a peer and expect the help will be repaid.

Individual Bonus (-ve)-> Experimentation - Experimentation allows a team to learn and improve through learning what succeeds and what fails. As people focus on meeting their bonus, and avoiding failure, Experiments are reduced and so is team learning and improvement.

Individual Bonus -> # of Features – Yay, a net good; we got more Features! But at what cost? ;-)

# of Features (-ve) -> Done - As the number of Features being worked on at any one time increases, there will be pressure to call them ‘Done’ sooner, even though they’re likely not done. The best part is, with a good bonus, this pressure doesn’t need to come from outside - the individual can create it for themselves.

# of Features (-ve) -> Quality – The more Features being worked on at the same time, puts increased pressure on the people doing the testing. This will have two effects: items will wait in a queue longer making their defects harder to fix, and more defects will slip through unnoticed. Reduced Quality will be the result.

# of Features (-ve) -> Peer to Peer Help - As the number of Features being worked on at any one time increases, there are fewer people who have capacity to help their peers.

Peer to Peer Help -> Throughput at the Bottleneck - We know from the Theory of Constraints that all systems have bottlenecks that limit its throughput. Bottlenecks are inevitable in a normal Agile environment, but when a bottleneck happens, we would expect another team member to help out until it is no longer the constraint for Throughput. If a bonus makes Peer to Peer Help less likely, Throughput at the Bottleneck will not improve.

Throughput at the Bottleneck -> Number of Features - If we improve the bottleneck, the number of features delivered will increase. Unfortunately, the use of bonuses means that there’s no incentive to help clear the constraint, so the bottleneck is likely to persist.

Peer to Peer Help -> Quality - Collaboration increases Quality through Pair Programming, Code Reviews, and even just having someone to bounce ideas off of. All this requires team members who feel that they have enough slack in their own work that they can help you. Bonuses ratchet up the pressure to meet a target and therefore reduce the amount of time anyone feels they have to provide help to others.

Done -> Quality - Scrum includes a Definition of Done as a quality leveler. Scrum challenges the team to ensure that level of quality is met whenever a Product Backlog Item is complete. As a team grows in skill, it normally strengthens its ‘Done’ criteria, therefore improving Quality. Unfortunately, in the land of bonuses and focusing on the # of Features, team members will feel pressure to skip parts of Done, as they feel it slows them down. Hint: over the long haul you never speed up by reducing quality standards.

Quality (Delayed) -> # of Features - When a team makes the effort to do quality work, through the Agile Engineering Practices, they increase the code quality. It is easier and faster to add new features in a code base where team members tidy up small messes and automate many of their acceptance tests. Unfortunately, in an environment where # of Features is consider a measure of success, corners get cut and quality degrades slowly.

Reviewing these results, we can see that bonuses might result in an increased number of features, but to stop analysis there is short-sighted and foolish. An increase in features doesn’t automatically lead to greater customer happiness. We should be focusing on Outcomes (features with good quality, that solved the customer problem) over Output (# of Features delivered). We may have got more of the target, but if the target was poorly chosen in the first place, the focus on it didn’t give us more of what we wanted.

Individual Bonuses can work in situations where we want competition. On a sports team, for example, a bonus for home runs might be helpful. Even here we have to be careful, because home runs alone don’t win baseball games. Bonuses may also help if there is a certain class of work that no one wants to do, for example update and maintain the build system. Again, this isn’t without consequences because, having provided a bonus for a mildly unpleasant task, all of sudden people will want bonuses for any task that is out of the ordinary.

In the context of Scrum and Agile teams we know competition is actively harmful and we want people to volunteer for the unpleasant tasks, so staying away from bonuses continues to be a good idea.

Team Bonuses

When we move bonuses to the Team level from the individual level, we reduce the competition within the team (Yay?), but now create competition between teams. The causal loop diagram won’t change very much. The effect of competition on things like cross-skilling will be reduced, but new elements will appear that affect cross-team dependencies and improvements.3

Thank You or Spot Bonuses

These are impromptu bonuses awarded to thank a team member for a particular success, such as delighting a challenging client or solving a really deep problem. These at least avoid the damage of encouraging changed behaviour to achieve the bonus, and they can have a positive impact on the team. But they still come with their own challenges.

- How to decide the recipient(s)? There is a risk that the award will acknowledge an obvious team member but overlook the contribution of someone else who provided invaluable ideas and advice but not hands-on work.

- Don’t reward overtime - this always backfires. Not everyone is able to do overtime (e.g. single parent or a team member going to school part time) so it creates unfair advantage. Overtime also leads to a variety of negative effects in the long run, both for the individual and the organization, so rewarding it sustains the harm.4

Fairness

Our causal loop diagram was already way too crowded, but fairness is another challenge. For many people, fairness is an important factor in motivation. (In the language of the SCARF Model5 this is a threat and reward). If members of the team feel that a bonus is unfairly awarded to one person for doing something (perhaps maintaining the build system) and the contributions of others are missed, they will feel unfairly treated. This will become a demotivator. I can’t readily imagine a case where the use of bonuses was a fairness motivator.

Conclusion

Bonuses are a bit like telling someone, “We value you enough to pay you X, however we will only pay you the last 10% of X if you jump through the following hoops.” Or, to use a different analogy, like large quantities of sugar where they taste great when we eat it, but the long-term effects are harmful. Bonuses attempt to improve performance by supplementing a person’s internal motivation with the allure of a sweet reward.

Instead of fighting against people’s internal motivation, find a way to align a team member’s own motivations with the needs of the team. When our team is working in an Agile way, this happens organically as part of the way we structure work.

The worst thing about bonuses is they seem so compelling in the short term but, when we add up all the delayed effects, it becomes clear just how insanely expensive bonuses are. So don’t waste money on a bonus scheme. They don’t improve performance. They destroy intrinsic motivation. Pay your people well and then give them the tools to find their own sense of motivation, and the performance results will follow.

Not yet convinced? You will be after you read this research that wasn’t conducted with an assumed target.

Research That Doesn’t Suck

Why Motivating People Doesn’t Work and What Does – Susan Fowler Intrinsic motivation—motivation that comes from inside us— is more sustainable than extrinsic or external motivation. The famous carrot or stick.

Self-Determination Theory in Work Organizations: The State of a Science – Deci, Olafsen, Ryan When our work environment has bonuses, the bonuses reduce the effect of the intrinsic motivation.

The first important finding in the meta-analysis by Cerasoli et al. (2014) showed that intrinsic motivation had a moderate to strong relation to performance across all studies and all types of performance, whether or not incentives were also being used. Accordingly, this indicates that intrinsic motivation is extremely important for the workplace. Furthermore, in line with the undermining effect of rewards on intrinsic motivation, Cerasoli et al. found that intrinsic motivation had a weaker effect on performance when incentives were directly salient, and a stronger relation to performance when the incentives were not directly salient.

The same paper shows that rewards help when the work is simple, but when the work is more complex (e.g. knowledge work) they don’t help at all and just interfere with intrinsic motivation.

In more nuanced analyses, Cerasoli et al. (2014) found that intrinsic motivation was a stronger predictor of performance quality, whereas extrinsic incentives were a stronger predictor of performance quantity. In a similar vein, Weibel et al. (2010) in their meta-analysis found that extrinsic incentives led to better performance on simple tasks but to poorer performance on more complex tasks. In short, PFP appears to be effective for motivating performance as quantity of simple, algorithmic tasks, but not performance as quality of complex heuristic tasks. Furthermore, PFP seems to interfere with the relation of intrinsic motivation to high-quality performance.

Do incentive systems spur work motivations of inventors in high-tech firms – Lazaric and Raybaut

Performance bonuses inspire competitiveness and resource guarding instead of teamwork and collaboration. The exact opposite of how we know Scrum — and productivity — thrives.

In a study of what happened to patent applications at Thales, a change in the bonus system: ”… harms relatedness and autonomy, reduces the creative output and knowledge diversity in an organization. In addition, changes to an existing bonus system may harm the culture it created: “new incentive system can conflict with intrinsic work motivation, notably because of the corporate imprinting. Instead of spurring work motivation, it may produce crowding out effects with a decline in motivations of some groups.”

Image attribution: Agile Pain Relief Consulting (Updated: March 2025)

Footnotes

Mark Levison

Mark Levison has been helping Scrum teams and organizations with Agile, Scrum and Kanban style approaches since 2001. From certified scrum master training to custom Agile courses, he has helped well over 8,000 individuals, earning him respect and top rated reviews as one of the pioneers within the industry, as well as a raft of certifications from the ScrumAlliance. Mark has been a speaker at various Agile Conferences for more than 20 years, and is a published Scrum author with eBooks as well as articles on InfoQ.com, ScrumAlliance.org and AgileAlliance.org.