- Home

- Sample Systems Thinking Conversation

Our Fictional Story

Horizontally Stratified Teams and 8-Hour Sessions

An architect in an organisation horizontally split into specialized teams (such as DBA or Reporting) describes a “vicious death spiral”. The project serves as a hub with an “absurd number” of external interfaces and dependencies. To the architect’s objection, the Scrum Master segregated the teams so that one delivers user stories while the other handles technical interfaces. This has resulted in grooming and planning sessions lasting over 8 hours because stories are not ready and technical staff engage in excessive deep dives. The architect is seeking a way to groom, slice, and size stories in under 10 minutes.

Marcus is a senior architect at a mid-sized software company where development is organized into horizontally specialized teams—database administrators in one group, front-end developers in another, a dedicated reporting team, and so on. He’s currently embedded with a project that sits at the center of the company’s ecosystem, connecting to what feels like an absurd number of external systems: payment processors, third-party APIs, legacy databases, and several internal platforms maintained by other departments.

When the project kicked off, Marcus raised concerns about the team structure. The Scrum Master, trying to bring order to the complexity, decided to split the work: one team would focus on delivering user-facing stories while a second team handled the technical integrations and interface work. It seemed logical on paper—let each group play to their strengths.

Six sprints later, Marcus describes what’s unfolding as a “vicious death spiral.”

Refinement and planning sessions now routinely stretch past eight hours. Stories arrive at these meetings incomplete, missing critical details about how they’ll interact with the technical layer. The integration team, trying to be thorough, launches into deep technical discussions that the story team can’t fully follow. Meanwhile, the story team keeps surfacing requirements that expose new integration challenges nobody anticipated. Dependencies ping-pong between the groups, and nobody feels confident enough to commit to estimates.

Marcus has watched team members check out mentally around hour five. He’s seen the same story carry over across three sprints because the slicing never quite works. The Scrum Master keeps extending the sessions, believing that more time will eventually surface all the hidden complexity.

Marcus is convinced there has to be a way to groom, slice, and size stories in under ten minutes. He just can’t see how to get there from here.

The Conversation

Claude

I’ll help you analyze this problem using the Systems Thinking skill.

Thank you for sharing Marcus’s situation. This is a rich example of how well-intentioned structural decisions can create unintended systemic consequences. Let me guide you through a systems thinking analysis.

Expanding the Perspective

Before we dive into solutions, let’s zoom out from the immediate symptom (8-hour planning sessions) to understand the larger system at play.

The hypothesis in systems thinking: The root cause of a problem typically originates outside the immediately visible context—not just within the planning room itself.

Let me start with a foundational question:

What organizational forces or constraints led to the decision to horizontally stratify teams in the first place?

In other words, what larger company structure, historical decisions, or business pressures created the environment where:

- Specialists are grouped by function rather than cross-functional teams?

- The Scrum Master felt splitting story work from integration work was the right move?

This matters because the team structure might be a symptom of deeper organizational patterns rather than the core problem. Understanding what’s upstream of this decision helps us see what forces might resist change—or where we might find unexpected leverage points.

What comes to mind when you consider the broader organizational context?

Mark

In the past, before Scrum, the whole organization was stratified by specialized teams. Since Scrum has come in, nothing has changed. Everyone says it is just more efficient.

Claude

Ah, now we’re getting somewhere. This reveals a critical pattern:

The organization adopted the ceremonies of Scrum but preserved the structure that makes those ceremonies struggle.

The phrase “everyone says it is just more efficient” is particularly telling—it points to an unexamined mental model that may be creating a self-reinforcing loop.

Probing the Mental Model

Let me ask you to examine that assumption: Efficient for whom? Efficient at what?

Specialized teams might genuinely be efficient at:

- Deep technical work within their domain

- Maintaining consistency in their area of expertise

- Utilizing specialized skills without “waste”

But what are they inefficient at? Based on Marcus’s experience, it seems like:

- Coordinating across boundaries

- Delivering integrated user value quickly

- Making decisions without extensive handoffs

- Actually completing stories end-to-end

Seeing the Feedback Loop

Here’s what I suspect is happening—a reinforcing loop (or “vicious cycle”):

- Teams are horizontally stratified →

- Stories require cross-team coordination →

- Coordination is hard and takes hours →

- This feels inefficient and painful →

- Leaders conclude: “We need better specialists and clearer handoffs” →

- This reinforces the belief in horizontal stratification →

- Back to step 1, only more entrenched

The system is producing exactly what it’s designed to produce. The 8-hour sessions aren’t a bug—they’re the predictable output of the structure.

Question for you: When people say “it’s more efficient,” what evidence are they using? Are they measuring:

- Individual utilization rates? (people staying busy in their specialty)

- Or actual throughput of completed, valuable features to customers?

This distinction often reveals where the mental model lives.

Mark

They’re measuring how much work (output) each person gets done.

Claude

There it is. This is a classic systems thinking trap called local optimization at the expense of global optimization.

The Invisible Costs

The organization is measuring output (how busy each specialist is) but not outcome (how quickly customer value flows through the system).

Here’s what’s likely invisible in their current measurement:

- Wait time - How long does a story sit waiting for the DBA team? The reporting team? Not measured.

- Coordination overhead - Those 8-hour sessions represent ~40-80 person-hours of cost per planning cycle. Not attributed to the team structure.

- Rework - When integration assumptions are wrong and teams have to redo work. Often invisible or blamed on “unclear requirements.”

- Opportunity cost - Features that never get built because the coordination tax is too high.

- Knowledge fragmentation - No one person understands the whole feature, so quality and innovation suffer.

The specialists look maximally efficient because they’re always working on something. But the system is profoundly inefficient because value moves through it like molasses.

The Reinforcing Loop Deepens

Now I can see an even stronger reinforcing dynamic:

- Measure individual output →

- Specialists stay busy in their swim lanes →

- This looks “efficient” →

- Coordination problems are blamed on “bad requirements” or “complexity” (not structure) →

- Solution: Add more process, longer planning sessions →

- People become MORE specialized to handle the “complexity” →

- Metrics continue to show high individual utilization →

- Back to step 1, with even stronger belief in the model

Marcus’s 8-hour planning sessions are the symptom of optimizing for the wrong thing.

Here’s a diagnostic question:

If you measured cycle time instead—the elapsed time from “story identified” to “value delivered to customer”—what do you think that number would reveal? And how would it compare to their current efficiency metrics?

Also, I’m curious: What’s happening to the people in this system? You mentioned team members “checking out mentally around hour five.” What are you observing in terms of morale, turnover, or people’s sense of effectiveness?

Systems often give us signals when they’re under stress—and human behavior is one of the clearest signals.

Mark

At the start of each big release people are enthusiastic. As release wears on, priorities change and the pressure to get everything done increases.

Claude

Now we’re seeing a temporal pattern—a cycle that repeats with each release. This is crucial.

The Release Cycle Pattern

Let me reflect back what I’m hearing:

- Start of release: High enthusiasm, fresh commitments

- Middle of release: Priorities shifting, dependencies surfacing late

- End of release: Intense pressure, people grinding to deliver

- (Implied) Post-release: Likely exhaustion, then… the cycle repeats

This suggests the system isn’t learning from its own feedback. Each release produces evidence that the planning assumptions were wrong (stories take longer, dependencies surprise people, priorities must change), but that evidence isn’t being used to change the approach for the next release.

A Critical Question: Why Do Priorities Change?

You mentioned “priorities change as the release wears on.” In systems thinking, we want to understand: What’s driving that change?

My hypothesis based on what you’ve described:

Are priorities changing because:

- Late-discovered dependencies surface during those 8-hour planning sessions, forcing re-negotiation of what’s feasible?

- The integration team discovers technical constraints that invalidate earlier story assumptions?

- External stakeholders react when they see the actual pace of delivery and realize their expectations won’t be met?

In other words: Are the priority changes reactive responses to the broken structure, rather than legitimate business pivots?

If so, here’s the vicious cycle:

- Release planning happens with optimism (not accounting for coordination overhead)

- Stories enter development, dependencies emerge late

- Things take 3x longer than estimated

- Leaders see they won’t hit commitments

- Priorities shift, adding chaos and rework

- Pressure increases to “just get it done”

- People burn out

- Next release: “Let’s plan better this time” → back to step 1

The system keeps trying to solve a structure problem with a process problem.

Question for you:

When a release ends—does the organization do retrospectives or post-mortems? And if so, what explanations do people give for why things took longer than expected?

Do they say:

- “Requirements weren’t clear enough”

- “We didn’t plan well enough”

- “The technology was more complex than we thought”

Or do they ever say:

- “Our team structure creates coordination overhead we’re not accounting for”?

This matters because it reveals whether the system is capable of questioning its own structure, or whether it just keeps blaming execution.

Mark

They tend to comment on the requirements because that is another department.

Claude

This is perhaps the most revealing insight yet.

The Blame Boundary

When the system consistently blames another department for problems, that’s a powerful signal. In systems thinking, we call this externalizing the problem—and it’s a major barrier to systemic change.

Here’s what’s happening:

- Requirements department → sends requirements

- Development (Marcus’s world) → can’t deliver efficiently

- Post-mortem conclusion: “Those requirements weren’t good enough”

- Requirements department likely concludes: “Development is too slow”

- Neither side questions the structure between them

This creates what’s called a “tragedy of the commons” or diffusion of responsibility:

- Requirements department optimizes for writing clear specs (their local metric)

- Development optimizes for specialist utilization (their local metric)

- No one is accountable for the end-to-end flow

- The coordination cost falls into the gap between departments

- Those 8-hour planning sessions are the visible manifestation of this invisible gap

The Self-Sealing System

Here’s the truly vicious part—the system now has built-in immunity to learning:

- Structure creates coordination problems →

- Coordination problems manifest as “bad requirements” →

- Blame goes to external department →

- Internal structure remains unquestioned →

- No change occurs →

- Back to step 1, with even more “evidence” that requirements are the problem

The system is now self-sealing. It has a ready explanation for failure that doesn’t require examining itself.

This is why Marcus feels stuck in a “death spiral.” It’s not just that the sessions are long—it’s that the organization’s mental model makes the true cause invisible.

A Leverage Question

Let me ask you something that might reveal a leverage point:

What would need to be true for someone to successfully say:

“The problem isn’t requirements quality—it’s that our horizontally stratified structure creates coordination overhead we’re not accounting for in planning or measurement”

Who would need to say it? What evidence would they need? What organizational forces would resist that message—and why?

In systems thinking, finding who benefits from the current structure (even unconsciously) often reveals the real barriers to change.

Mark

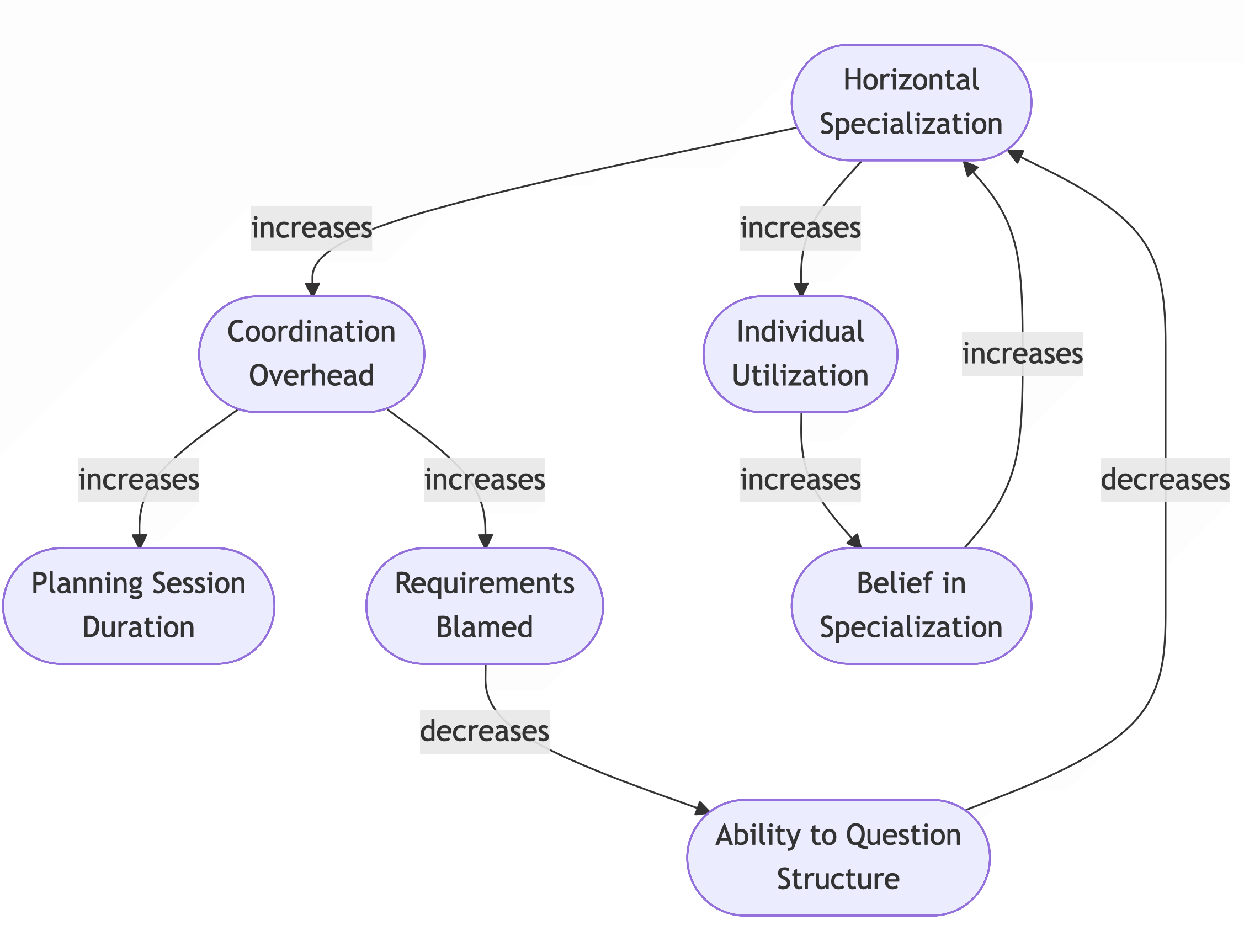

Before we go any further let’s visualize what we have so far with a Causal Loop diagram.

Claude

Excellent idea! We’ve surfaced enough interconnected variables and feedback loops that a visual representation will help clarify the system dynamics.

Key Variables We’ve Identified

From our conversation, here are the main things that vary over time:

- Horizontal Specialization - degree to which teams are organized by technical specialty

- Coordination Overhead - effort required for cross-team collaboration

- Planning Session Duration - time spent in grooming/planning

- Individual Utilization - how busy specialists appear (what’s measured)

- Belief in Specialization - organizational conviction that specialists are “more efficient”

- Requirements Blamed - tendency to blame external departments

- Ability to Question Structure - capacity to examine the team organization itself

Mapping the Key Reinforcing Loops

The Three Vicious Cycles

R1: The Self-Sealing Loop (top path)

- Horizontal Specialization → Coordination Overhead → Requirements Blamed → (reduces) Ability to Question Structure → Horizontal Specialization persists

- The story: Specialization creates coordination pain, which gets blamed on “bad requirements,” which prevents anyone from questioning whether specialization itself is the problem. The structure becomes immune to examination.

R2: The Local Optimization Loop (bottom path)

- Horizontal Specialization → Individual Utilization appears high → Belief in Specialization grows → Horizontal Specialization increases

- The story: Specialists stay busy (high utilization), which “proves” the model works, which strengthens commitment to specialization. The wrong metric reinforces the wrong structure.

R3: The Planning Spiral (middle feedback)

- Coordination Overhead → Planning Session Duration increases → More Coordination Overhead (people become more disconnected)

- The story: The attempted “solution” (longer planning sessions) actually makes the problem worse by taking people away from collaborative work.

What This Reveals

These three reinforcing loops work together to create Marcus’s “death spiral”:

- The system can’t learn (R1 blocks structural questions)

- The system thinks it’s working (R2 shows “good” metrics)

- Attempted fixes backfire (R3 creates more of the problem)

Critical question: Looking at this diagram, where do you see potential leverage points? What would need to change to break or reverse one of these loops?

(Note: We could add more complexity—release cycles, morale, late dependencies—but I want to check if this core structure captures what you’re seeing first.)

Get Certified

Explore what Scrum is and how to make it work for you in our Scrum Certification training. Hands-on learning will guide you to improve teamwork, deliver quick feedback, and achieve better products and results.

Registration is now open for workshops:

About this course

Focuses on the role of the team and the ScrumMaster. Get the skills and practical experience necessary to improve teamwork, take the exam, and advance your career with a certification that is in high demand today. Often the best fit for anyone new to Scrum.

Learning and Benefits

Relatable Scenarios

Learn on-the-job applications of key Scrum concepts, skills, principles, along with practical solutions that you can apply the next day for difficult, real-life situations.

Respected Certification

Everything you need to earn your Scrum Alliance® ScrumMaster certification, including exam fee and membership, and so much more.

Practical Exercises

With focus on the challenges that real teams face, and tools to dig deeper. You don’t need more boring Scrum theory. You need something you can sink your teeth into to see immediate results.

Jargon-Free Learning

This workshop is not just for software development or people with a computer science degree. We’ve helped many non-software teams with Scrum.

Career Advancement

Use Scrum knowledge to standout at work, get paid more, and impress your customer, all without burning out.

GenAI for Systems Thinking

Learn the basics of using Generative AI as a tool to support Systems Thinking in your ScrumMaster role. Explore how to leverage GenAI to help uncover patterns, and think more deeply about the systems your team operates in.

Ongoing Support

Your learning doesn’t stop when the workshop ends. You get lifetime access to all course materials, plus a followup email series designed to reinforce your learning objectives and help you apply what you’ve learned on the job.