What United Can Teach Us About Building Systems

![By InSapphoWeTrust from Los Angeles, California, USA (United Airlines - N797UA Uploaded by Altair78) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](/_astro/800px-United_Airlines_777_N797UA.BcdaNnsO_ZBsmMy.jpg?dpl=6966b6de4c38040008093c37)

In April 2017, United Airlines made global headlines when they forcibly removed one passenger (David Dao) who had already boarded the flight, to accommodate crew flying to another destination. The flight staff called the airport police and Dao was hurt as he was dragged off the plane, suffering a concussion, loss of teeth and other injuries.

In the same week, another United passenger flying from Hawaii to Los Angeles was forced off a plane despite having paid full fare for a first class ticket. “That’s when they told me they needed the seat for somebody more important who came at the last minute,” Geoff Fearns said. “They said they have a priority list and this other person was higher on the list than me. They said they’d put me in cuffs if they had to.”

Neither of these cases should have ever happened. In both cases, crew on the ground and then customer service handled the situation badly. However, I don’t think that the real issue is the airline staff.

There are at least three major issues at play:

- Working at 100% of Capacity

- Too many conflicting rules

- Culture

Working at 100% of Capacity

David Dao was removed from his flight because four crew showed up after the passengers had already boarded. The crew were required in Kentucky the next day, and their absence would have delayed several hundred passengers on other flights. United offered up to $800 to get people to leave the flight, and then when that didn’t work, they simply selected four passengers at random to be removed.

There are two significant problems here:

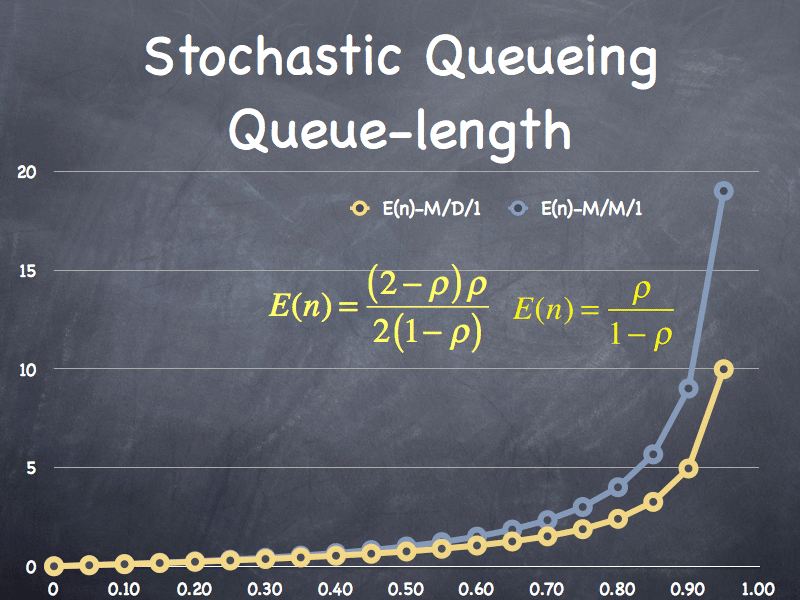

- By attempting to have every flight 100% full, there is no capacity to respond to small things going wrong in the system. E.g. extra people showing up at the last minute and creating a shortage of seats. This shows up time and time again, when utilization of capacity in a system exceeds a certain point and the system becomes fragile or breaks completely. In highways and road systems, it happens at around 65-70% of the designed capacity of the road.

- By having only enough crew in each city to survive that day’s flights, United is again running at 100% capacity with respect to crew. There is additional risk in that a small problem in Chicago would escalate and become a big problem in Kentucky 24 hours later.

The issue in both cases is the attempt to squeeze every last dollar out of a situation. When we design organizations or systems (e.g. highways, hospitals, airlines) we need to build in enough slack to deal elegantly with small problems.

United could avoid this problem in the future. On all flights to key destinations, set aside 3-4 seats for deadheading crew, and offer these seats to standby passengers only when it can be guaranteed no crew will show up. Another alternative would be to establish backup crews in each city the airline services – the challenge there would be ensuring the backup crews have sufficient cross-skilling to deal with the variety of aircraft that United fly from that airport.

When we’re building teams for knowledge work (e.g. Software Development, Marketing, etc.) that slack time can be used for learning and growing skill.

Too Many Conflicting Rules

The more rules that a system has, the more unanticipated effects, and the less freedom the people doing the work have to make sensible decisions. Between the two incidents, we can see that United has some complicated rules about what it actually means to have bought a fare on the airline:

- more important First Class passengers trump other First Class passengers

- disabled people, children travelling alone and high status passengers trump deadheading crew

- deadheading crew[1] have priority over Economy passengers

- United Ground Staff are authorized to offer $400 and then $800 to get passengers to disembark, and cannot deviate from that

This list of United’s policies is, of course, incomplete as it’s just gleaned from news reports following the incident. The complete list is undoubtedly much longer.

With all these rules in place, the ground staff didn’t have enough room to explore other options. Perhaps if they had offered $1000 out of the gate, they would have got volunteers more quickly. Strangely, having to offer $400 – an insultingly low sum for many travellers – made it less likely that people would accept any subsequent offer.

As we learned in Simplicity, when we design systems with complicated rules, they will break down. When we build systems with simple heuristics, people have more capacity to make better decisions in their current situation. In most cases, they use the heuristic as expected, and only occasionally do they break it where local circumstance justifies.

Culture

Under the control of Jeff Smisek, United went from an airline with some customer focus to one totally focused on costs and the bottom line.[2] Companies that focus on reduction of cost might do well in the stock market for a few quarters. They do well because profits increase, but in the long run the focus on trying to save pennies hurts because it leaves an organization that has no flexibility.

Build an organization that is focused on delighting the customer[3], and give the team real decision-making capacity. Then even if we’ve made mistakes, those people still have the ability to identify a problem as it happens and make the situation right.

By all accounts Oscar Munoz, United’s CEO, is attempting to turn the culture around. He has only been CEO for 20 months, which is not enough time to make a significant impact on a company employing nearly 90,000 people.

The real question: is Munoz attempting to make significant changes to affect the culture, or will the cost focus of his predecessor live on?

Footnotes

- Deadheading crew – flight staff who aren't working on the flight but are instead flying to the destination in a passenger seat, to work a flight from there.

- The Root Cause Of United’s Denied Boarding Fiasco

- Is Delighting The Customer Profitable?

Mark Levison

Mark Levison has been helping Scrum teams and organizations with Agile, Scrum and Kanban style approaches since 2001. From certified scrum master training to custom Agile courses, he has helped well over 8,000 individuals, earning him respect and top rated reviews as one of the pioneers within the industry, as well as a raft of certifications from the ScrumAlliance. Mark has been a speaker at various Agile Conferences for more than 20 years, and is a published Scrum author with eBooks as well as articles on InfoQ.com, ScrumAlliance.org and AgileAlliance.org.