What Are the Limits of the Scrum Framework?

Where is Scrum Applicable?

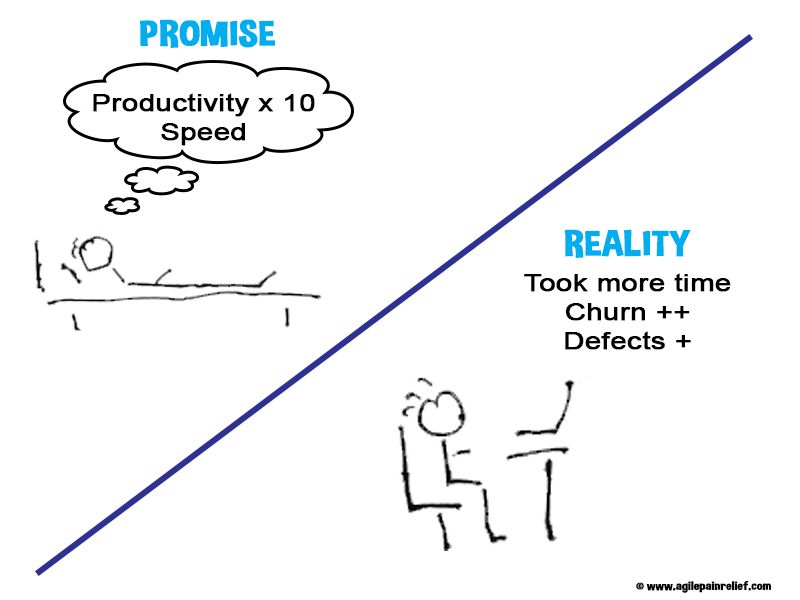

Scrum is a tool for building autonomous, self-organizing, high-performing teams and organizations which can successfully respond to changing business circumstances. People often choose to use Scrum because they want higher quality or greater speed, not understanding that these are outcomes of high-performing teams and not of Scrum itself.

Scrum has been used effectively with teams in a diverse array of industries, including Software Development (where it grew up), Hardware Development, Manufacturing1, Marketing2, HR… even Fighter Planes3 and Gas Plant Design4! What these very different industries have in common is they rely on a form of knowledge work, which can be understood as work that primarily involves non-routine problem-solving that often needs creative thinking. Knowledge work benefits from collaboration, which is the primary focus of Scrum Teams, so it’s no surprise that Scrum is well-suited for these industries.

Since teams are the core work unit of Scrum, many of the limits of Scrum come from the focus on how an organization’s teams are structured.

Key Conditions for Scrum to Work Well

Understanding now where Scrum is effective, we can consider what structural foundations are needed for it to function well in a given work environment.

Knowledge Work – It may seem obvious but it’s worth stating: organizations (including most retail and service industries) based around the performance of routine tasks that do not require complex problem-solving or creative thinking will not benefit from using the Scrum framework.

Common Goal – A group of people only becomes a “team” when there is a common goal or target that they’re attempting to achieve. In Software Development, the common goal comes from the Product Vision and Strategy. In a Marketing team, this might come in the form of a brand strategy or marketing campaign plan. Whatever the industry, the goal must unite the work of all team members to something greater than their individual contributions. Without a common goal, there isn’t really a cohesive team, and cohesion is key.

Sufficient Challenge – In tandem with a Common Goal, the problem must be challenging enough that people can’t get the job done if they work alone. If people can work without interacting with others and still achieve their goal, they will often choose to do that. The difficulty of the problem must warrant the use of teams, otherwise Scrum is just unnecessary overhead.

Dedicated Team Membership – The costs of multi-tasking have been documented on numerous occasions and it’s no longer considered a desirable skill like it once was thought to be.5 Assigning people to work on more than one team forces them to multi-task, making them less productive. Any form of multi-tasking causes people to lose capacity. Assigning them to multiple teams is just the worst case. Their capacity is reduced due to the delays and costs to focus as they switch gears from one context to another and the teams suffer bottlenecks as they wait for their turn with that person. Ultimately, the number of errors will increase, in part because these individuals switching context will forget key details. Evidence shows that dedicating people to one team, and only one team, doubles the throughput of all teams involved.6 Without Dedicated Team Membership, all groups are destined to a lower level of productivity and true teams – certainly not high-performing ones – never form. Scrum would be significantly shackled in this environment.

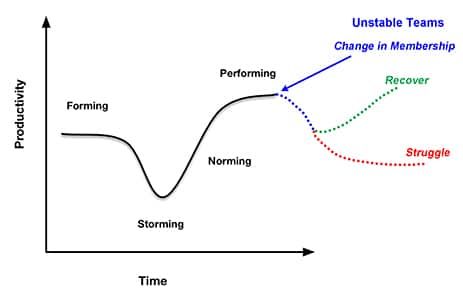

Stable Team Membership – Effective teams take time to form. It takes 6-8 months before a new team develops the cohesion necessary to be truly effective. Furthermore, every time there is a change in membership the team takes a temporary drop in productivity. After a few months, they may regain strength, and may even eventually improve, however some teams never recover. In situations where there is frequent changeover in team members, the team will always be stuck at a lower level of performance. In addition, Stable Teams are a requirement for predictability.

Low Cost of Change – Agile came of age as the cost of making changes in software was being drastically reduced. Much of the work in the years since has been focused on further reducing the cost of making change – from Continuous Integration and Test Driven Development to DevOps and Behaviour Driven Development. The cost of change in modern software development work isn’t zero, but it is considerably lower than the green screens78 and mainframes. For any flavour of Agile to succeed in a new environment, reducing the cost of change (even late in the game) needs to be a priority. In work that incurs a significant cost if changes are made, Agile/Scrum isn’t going to be as practical.

Plannable – Scrum Teams normally work in two-week Sprints, so they need to be able to plan their work at least that far in advance and allow for accommodating small changes. For example, a software development team gives itself enough flexibility that it can fix a production support issue mid-sprint without derailing the main work of the Sprint. A marketing team could adapt their campaign in response to new data it received about customer behaviour. The practical limit is that at least half of the teams’ work needs to be plannable. Companies whose entire business model is to respond to unpredictable client needs won’t benefit from using Scrum to organize future work. Caveat: outside the repair industry there are few businesses that survive in the long run on a purely reactionary basis.

Empowered – Teams can only form when team members feel that they have autonomy. Scrum makes this explicit by establishing the team as self-organizing. Hopefully, this is never a key condition that is lacking but, if it is, trying to apply Scrum wouldn’t help the team become self-organizing and efficient, but it may expose the problem, so it can be resolved before continuing further.

Cross-Skilling is Possible – Scrum (and Kanban teams) eliminate bottlenecks by sharing skills until delays can always be addressed by multiple team members. Bottlenecks are such a fundamentally important barrier to high performance that organizations eventually must address them. Toyota’s approach is to pay people more to be able to handle multiple stations. In healthcare, there are some jurisdictions starting to address the issue by allowing some work previously only done by doctors to now be done by nurses or nurse practitioners. At the same time, there are some work environments where, due to regulation, law, or radically different skill areas (e.g. artist and metal worker), cross-skilling may be limited in its applicability or value, limiting the value of Scrum as well.

Early Delivery and Testing – In Scrum, we don’t assume our expectation of the User needs are correct. Instead, we prefer to deliver products early and gather feedback. We operate in a mode of Product discovery rather than creation. In an environment where we fail to deliver a working product at the end of every Sprint, we are unable to gather feedback. The solution is to find something to show and gain feedback on at the end of every Sprint.

Co-location – Having all team members in the same room continues to be the best choice. Humans have evolved over millions of years for face-to-face interaction, so this is still the best way to build collaborative teams. While remote work and distributed teams are currently trendy in many businesses, the challenges these create are significant and result in high-performance taking longer to grow in the Team. If distributed teams are absolutely unavoidable, applying Scrum practices (e.g. daily stand-up) will be more challenging and require adaptations. It’s still possible to practice Scrum effectively in distributed teams – it’s just much harder.

Examples of Where Scrum Isn’t Ideal

So now that we understand why Scrum works and its conditions for success, these are in order from teams where Scrum is the least likely to help, to where it will be challenging but may still offer some benefits.

Construction - When a team is tasked with pouring concrete or paving a road, the cost of change is effectively the cost of the work. Agile approaches, in general, can still work, but it comes with an increased cost. Consider Lean Construction and both the Empire State Building9 and the London Shard10 of examples of this approach.

Help Desk and Repair Services – When people in an organization provide digital or phone-based support services, their work does involve the Knowledge Work key condition, but it’s entirely driven by interruptions. They can start the day working on one issue, but when a call comes in with a more important issue then they must switch. This pattern can repeat itself several times during the day. This violates the Plannable condition, so Scrum won’t be effective in this context. Consider a different tool that improves the flow through any system, such as Kanban. This may also apply to other organizations and services – essentially anywhere that knowledge is the primary requirement, but the work is not plannable.

Back-Office Operations – Many organizations have groups that do all the background work such as finance and other related departments. Most of this work – invoices, expense tracking, and other bookkeeping – is done effectively by individuals working on their own. While the work is knowledge-based, it is often repetitive and so wouldn’t be Challenging. These groups often lack a coherent vision or Common Goal. Consider Kanban instead of Scrum again, as a tool to better understand the flow of work inside these groups.

Infrastructure and Technology – Most organizations also have people who configure laptops, servers, security, networks, firewalls, and other technical infrastructure. This knowledge work is less repetitive and more Challenging than back-office work, and it benefits from collaboration because problems often require more than one skillset to solve. These groups also typically have a Common Goal (e.g. keeping internal users productive and safe). But in many cases, their unplanned work exceeds their Plannable work. However, Scrum might help by bringing into focus the volume of the unplanned work for the team, helping them put effort into reducing it.

COTS Apps11 – Organizations often outsource a lot of their backend software (think: Gmail, QuickBooks, Expensify) to cloud vendors. This is fantastic, but eventually, there are enough applications each that requires occasional changes (new user, new accounting rule, etc.). None of these applications requires one person maintaining them as a full-time job, so you might end up with 6-7 people maintaining 10-15 individual applications. Lacking a clear Common Goal, this group is unlikely to become a Team. Scrum could work but the value might be limited. The challenge for both the infrastructure and teams is that their knowledge is likely to stay fragmented since there is little reason for people to learn another team member’s area. Whether the team chooses Scrum, Kanban, or some other framework, this will likely remain an issue. Consider asking if the group could be reorganized to create a space where a Common Goal is possible. An alternative option is the team could work to create a goal that is possible in their circumstances. These notes are inspired by a conversation with Petri Heiramo:

Given the “product” they work on is clearly not sufficient to rally them, the discussion would need to be shifted to something greater than the work they are doing. Would they want to become the best support team ever? Would they want to do whatever they are doing in half the time? Would they want to NOT do their work and try to automate as much of it as possible? Do they know whose lives they are making better and could they possibly derive some worthy goal from that end?

One possibility would be to ask them how happy they are at work. If they’re not happy, the next question could be are they willing to put effort into making themselves happy. After all, their three main choices are 1) keep doing what they are doing and stay unhappy, 2) do something to make themselves happier and proud of their work, or 3) leave the company for something else. Obviously, 3 is not desirable and not a great starting point, so the choice should really be between 1 and 2. Then the next step could be to ask them what makes them happy and proud at work, and/or what makes them unhappy and ashamed. This could help them establish a shared goal of becoming happier and discover a starting point for corrective action. There could be a discussion of how to measure happiness and pride (i.e. how to know they’re making progress toward their goal). There could be an agreement of some self-reward (like beer on Friday) whenever they’ve achieved some concrete improvement in their work that they are proud of such as:

removing the deepest information bottlenecks that prevent them from taking holidays without stressing about work.

clearing up their worst technical problems.

making a grumpy customer happy or even delighted with their team/service.

establishing some new practice to improve productivity, or reduce feedback cycles.

Individual Work – any business problem where there is no prospect for collaboration (company of one or everyone works in isolation), won’t benefit from Scrum directly. After all, there is no team to grow. In that circumstance, consider Personal Agility and Personal Kanban.

Team Members Matrixed onto multiple teams and no Stable Membership – I can’t imagine a business circumstance where this is desirable. If this is the scenario, Scrum will work quite effectively to highlight the organizational impediment, but not to help manage the problem. In every workshop, we discuss the fact that Scrum is a tool for finding problems. Scrum succeeds in the long run when the organization takes seriously the need to resolve issues like this that Scrum finds, not just manage them.

There are limits to what we can use Scrum for, but they’re much wider than most would imagine.

Thanks to Petri Heiramo for suggestions and the visioning exercise for the COTS team.

Want to Learn and Become a More Effective ScrumMaster?

Practicing Scrum in the real world is challenging. Questions like whether Scrum is the best choice for a given project or organization is something most of us learn from spending years working in the field… and failing.

We understand that desire to gain a deeper understanding of Scrum: why we choose Scrum and how to apply it effectively. If you share that desire, we invite you to join us for one of our Advanced Certified ScrumMaster workshops – a collaborative, hands-on experience with Certified Scrum Trainer Mark Levison, who will coach you through the most complex aspects of using Scrum, on how to spark real change in your organization, and on what to do to advance your career as a Scrum coach.

Image attribution: Agile Pain Relief Consulting Updated: April 2025

Footnotes

Mark Levison

Mark Levison has been helping Scrum teams and organizations with Agile, Scrum and Kanban style approaches since 2001. From certified scrum master training to custom Agile courses, he has helped well over 8,000 individuals, earning him respect and top rated reviews as one of the pioneers within the industry, as well as a raft of certifications from the ScrumAlliance. Mark has been a speaker at various Agile Conferences for more than 20 years, and is a published Scrum author with eBooks as well as articles on InfoQ.com, ScrumAlliance.org and AgileAlliance.org.