Impact Mapping – What It is, in Depth, with Examples

Work is humming along nicely when your Marketing VP stops by your desk and says, “We need to double monthly sales.”

That’s it. That their entire instruction.

After you recover from this bombshell, you will need to decide what tool you will use and who you will grab to help you start to tackle this problem.

Do you use Story Maps? (A great tool when you have an idea of where you’re going.) A Journey Map? (Also requires that you have an idea of where you’re going.) A Traditional Roadmap?

I’m going to suggest that you create Impact Maps in situations like this, where you have a vague goal but haven’t yet done a good exploration of how to get there. Impact Mapping is a tool to help you figure out where you will likely get the most bang for your buck. You map out some options to achieve a goal. Once you’ve got a rough idea, you stop mapping and execute.

What is Impact Mapping?

Impact Mapping is a strategic tool to help teams and businesses focus their work on a product feature that will give the most bang for their buck. I’ve used Impact Maps for teams seeking to figure out what/where to build next, and I’ve also used them outside of software development. It is a tool to help the Team and the Stakeholders visualize the outcome they want, the people who can help them achieve it and the deliverable. By visualizing the choices, the team are better able to decide what to create first.

Why Impact Maps Help the Product Owner and Product Manager

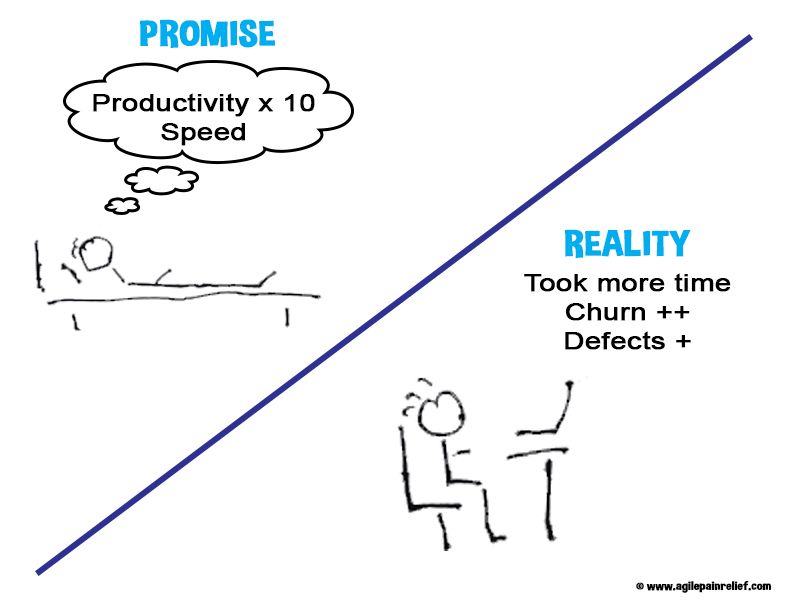

Many organizations struggle trying to use Traditional Roadmaps in an Agile environment. They don’t work because there is an implied linear flow and promised timeline for delivery. Linear plans of this nature aren’t suitable in our current world, where change can happen at a rapid pace and history often isn’t a predictable indicator (e.g. COVID, or when once-in-a-hundred-year floods occur twice in three years). Impact Maps replace Roadmaps, making it clear that we have choices in deliverables, while still achieving the original goal.

Traditional road-mapping approaches:

- Assume that everything will go well.

- Don’t put limits on the number of goals that will be achieved. This lack of bounds puts undue pressure on the team for things that might not even remain relevant.

- Don’t ensure the Team and the Product Owner have the same understanding of the strategic goals.

Impact Maps, on the other hand, are about finding the features/work that will have the biggest impact for the customer.

How do you know which strategic options to tackle first? As humans, we tend to jump from a goal to the actions that we think will help us achieve it. Impacting Mapping works by forcing us to consider who is involved in achieving our goal and how they can help us. Using this approach, we find a broader set of possible options –including some that we might not have considered– before narrowing down on which option is most likely to help achieve our goal.

When faced with a variety of options, mapping makes clear which option will have the largest impact and therefore which one to tackle first.

Impact Mapping is a tool to help you figure out where you will likely get the most bang for your buck. You map out some options to achieve a goal. Once you’ve got a rough idea, you stop mapping and execute.

How to Use Impact Maps

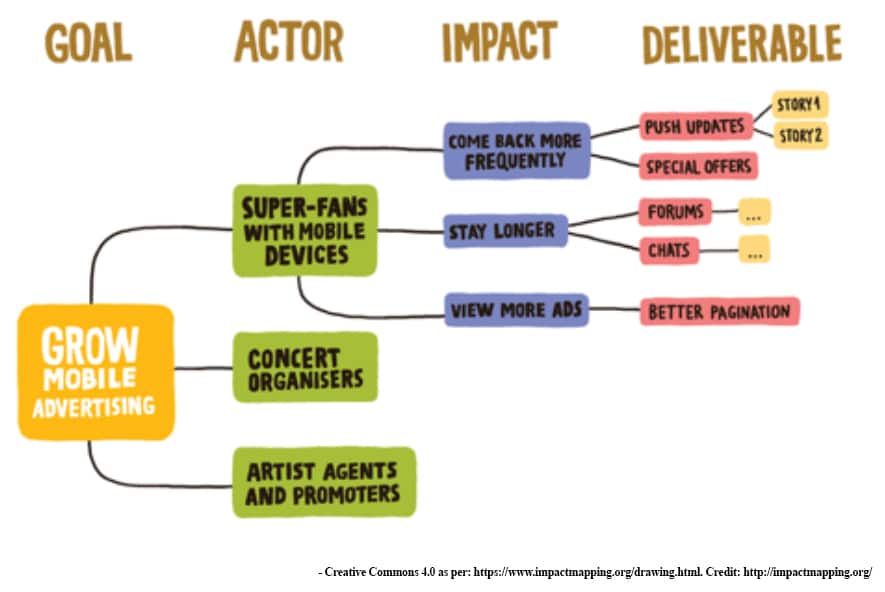

Identify the Goal first, then Who (Actor), How (Impact), and What (Deliverable).1

1. What is the Goal in an Impact Map?

The Goal answers: Why are we doing this? What are we attempting to achieve? The map will be focused on finding options or ways of accomplishing that objective.

2. What is the Actor/Who in an Impact Map?

Who are the consumers or users of our product? Who can produce the desired effect toward our Goal? Who can obstruct it? In describing the Who or the “Actor”, the order of preferred usage is: specific individual, persona, role, job title, group/department – from most specific to least specific. Consider users of the system first, stakeholders second. By focusing on specific people or personas, it makes it more likely the deliverable will meet a real person’s need.

3. What is the Impact/How in an Impact Map?

What Impact can the Actor have? How can they help achieve our Goal? How can they obstruct progress towards the Goal? These are the Impacts that we’re trying to create or prevent. Don’t list everything an Actor might do – just the key things. List business activities, not process features. Be specific and consider negative outcomes as well as positive. When used in an Agile environment, the Impact/How can be tied back to the value statement in a User Story. Check to ensure that both are aligned.

4. What is the Deliverable/What in an Impact Map?

What can we do as a team to deliver the Goal? These become the product features. These Deliverables are the least important end of the spectrum and, on the first pass, will be unrefined. Much of software development is done when someone powerful wants a feature because they think it’s a good idea, but they haven’t really proven the idea will deliver value. By placing Deliverables after the Impact, wasted resources are avoided. So evolution here is a good thing. We don’t need to find all the Deliverables, just enough to find a deliverable that will, for lower cost, deliver the highest Impact. If an early attempt at delivering value fails, we can always return to the map with new information and try again.

Example of an Impact Map:

Figure 1 - Creative Commons 4.0 as per: https://www.impactmapping.org/drawing.html. Credit: http://impactmapping.org/

Tips for Drawing an Impact Map

Impact Maps are intended to be drawn and not just written in words. Visualizing them helps make conversations more concrete. It makes it easier to understand the relationship between a deliverable and the Actor who it is for. If you’re not yet familiar with them, creating an Impact Map from scratch can be intimidating, but it doesn’t have to be. This simple process helps move you through it, and often works well when done over two separate sessions by a collaborative group that includes stakeholders, the Product Owner, leadership and the people who will be doing the work:

Session One: define expected business Goals and measurements Session Two: build the map

Session One: This is the preparation session.

1. Identify the core business objective. Do this by listing possible business Goals, and discussing which one is the current priority. Goals often tie back to money (how to save money, make money, or protect money). However, Goals may tie back to other tangible benefits such as number of readers for a book; improvement in the team’s morale, etc. All of these are measurable in a meaningful way and, if achieved, would make a positive difference in their context. To find real Goals, ask: Why is this feature important? Or: How would it be useful? Keep iterating until you find the underlying Goal. 2

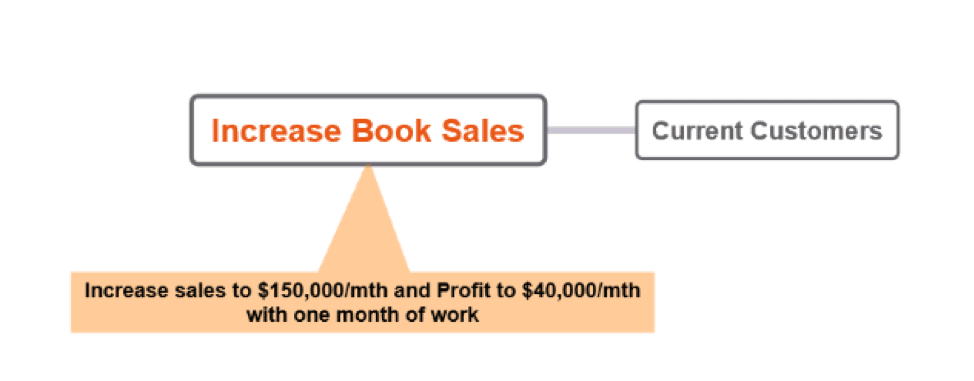

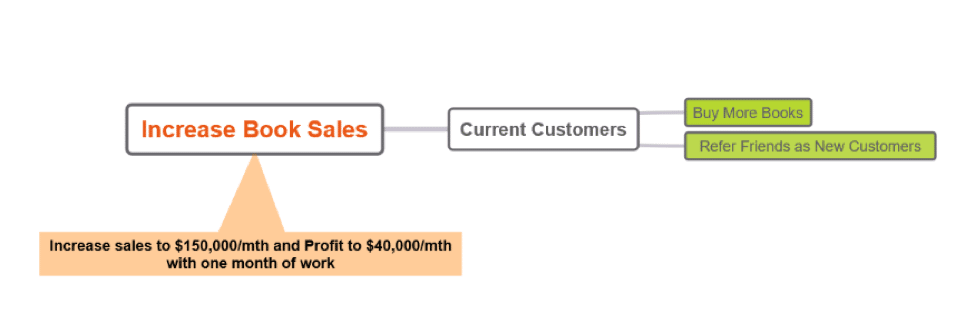

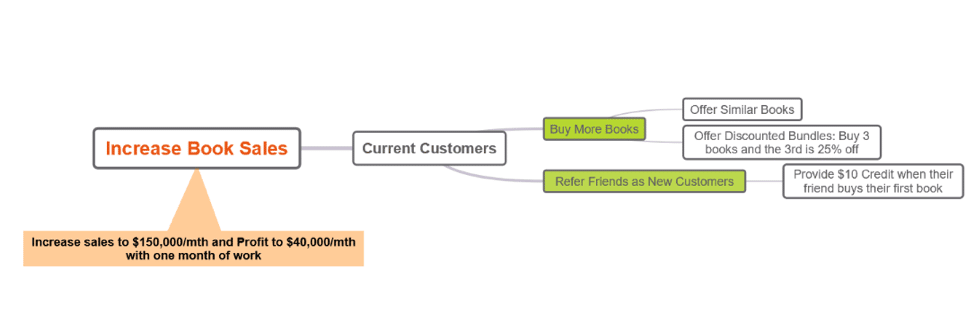

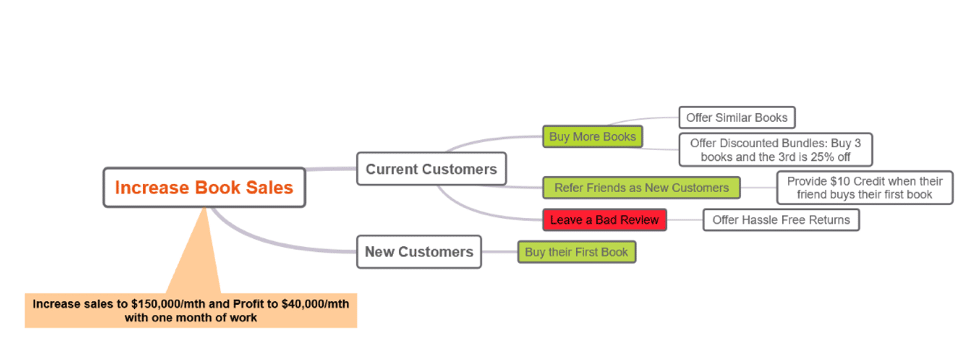

Using the fictional company of our Scrum by Example team, our Impact Map example Goal is: Increase Monthly Book Sales and Profitability for the World Smallest Online Bookstore

2. Define good measurements.3

-

- what we’ll measure (aka the ‘scale’)

- how we’ll measure it (aka the ‘meter’)

- what the current situation is (aka the ‘benchmark’)

- the minimum acceptable value (e.g. the break-even point)

- for investment (aka the ‘constraint’)

- and the desired value (aka the ‘target’)

- what we’ll measure (aka the ‘scale’)

Our example: ● Measure - Monthly Sales, Monthly Profit ● Current Situation – $100,000, Monthly Profit $20,000 ● Minimum Acceptable Value - $125,000, Monthly Profit $30,000 ● Investment: $200,000 (e.g. one month of expenses for one team) ● Desired Value: $200,000, Monthly Profit $70,000

3. Plan the first milestone. Effectively, you’re picking a Goal/target combination.

Our example: One month after the team complete this work they have increased sales to $150,000/month and profit to $40,000/month. Since the investment is also one month of working time, we’re looking for payoff in two months’ time.

Session Two: This is the mapping session.

1. Draw the map skeleton. Start with one Actor (Who), Impact (How), and Deliverable (What). Use tools that promotes collaboration – whiteboard, sticky notes, etc.

-

- Put the milestone (Goal/target combination) in the center.

- Find the Actors who could have a positive or negative effect on the milestone.

- If people already have ideas or features, put them around the outside. Then ask some questions: Does the feature contribute towards the Goal? Is the Impact valid for the Actor it is ascribed to? Gojko offers a user story-like technique for testing: “<someone> can help us achieve our <objective> by doing <something differently>”

- Put the milestone (Goal/target combination) in the center.

Then we ask ourselves: What “Impact” can the Actor have? Or: How can the Actor help us?

What Deliverable could we build to achieve this?

2. Find alternatives. What else could these people do for us? Who else can help? Who can obstruct? If you find that you’re struggling, try Hohmann Innovation Games4 or Gray Gamestorming5. Also try asking which of the following factors to consider: New Business, Upsell, Retainment, Operational Efficiency6

3. Identify key priorities. Look for obstructions. What can stop us before we start? Is there high-value, low-hanging fruit? What key assumptions should be tested? These questions should all be focused on business activities, impacts, and outcomes, not software features.

In our example, questions we might ask: Are we currently getting bad reviews or negative comments through support? If so, is there a common theme? Do these issues harm our relationships with our current customer. (Retainment)

Assuming our customer relationships are in a good place, will we have happier customers if we sell them more books? (Upsell) Or will we have happier customers if we offer them a referral bonus for referring friends? (New Business)

Alternative: Prioritization. Select which Actor to satisfy first. Consider modified dot voting (red dots for critical features, green dots for low hanging fruit). Given the limited number of options, you can use a Kano model7 to categorize more effectively. The Actor with the fewest red dots gets prioritized.

4. Earn or learn. Set a budget to learn whether or not a Deliverable will have the expected Impact. Use simple tools (often not software) to test the value or assumption. The sample questions will be very similar to those used in Lean Startup.

-

- What is the simplest way to support this work?

- What alternatives are there?

- What is the simplest way to test this assumption?

- Could we start earning money with a manual process?

- What is the simplest way to support this work?

If you’re struggling to find testable slices, try story mapping or Gojko’s Hamburger method.8

Our example: Can we test any of these ideas without implementing a feature in software? For example, can we offer hassle free returns simply by adding a note on the site or in every order saying if you need to do a return call support? This is an experiment – if no one uses the offering maybe it’s not valued.

“Offer similar books” requires a lot of work as we require some algorithm to guess which books are similar. Is there a simple version of this feature that we could try to start? Maybe we could look at our ten bestsellers, manually find books that are close to them, then when a top seller is purchased, offer the companion book. This experiment still requires software development work, however the cost has been reduced from several Sprints of work for one team, to a version that could be built in one Sprint.

Fit the Measures to the Impact Map

Risks

It’s important to make sure that the Impact Map itself doesn’t becomes the target, where we might risk missing things that matter but that are outside the picture.

Typical challenges and mistakes

- Too many people involved in creating the map – too large a group will reduce the diversity of the opinions and ideas shared, as the quieter people are drowned out

- Wrong people (e.g. no decision makers, no technical people)

- Projector or one person doing the drawing. Impact Mapping is a collaborative technique. If you meet in person, consider using sticky notes or index cards and move items around on a table. In a virtual context, consider an electronic whiteboarding tool that invites contributions from everyone versus a tool that only one person can update.

- Early criticism (we want more ideas while still in the divergent phase[9] , not an attempt to prune)

- Leaders with outsized influence (leaders should always speak last)

- Reverse engineering of the entire shopping list. Your existing list of preferred Deliverables may not map well to Actors/Impacts.

- Drilling down to detail too early

- Skipping levels in the Goal, Actor, Impact, Deliverable layout

- Building a map without metrics to guide

Impact Mapping and User Stories

Many Agile Teams use User Stories as dumping ground for ideas, such as when someone has a technical need or a pet feature that they would like to see delivered. They express the idea in the format “As a <role>, I want <to do> so that <value>” and dump it the Product Backlog. Impact Maps can be used to keep these User Stories honest. If the User Story doesn’t map to a branch of the Impact that we’re prioritizing, then it can be dumped.

Impact Mapping and Scrum

As we’ve seen, mapping is a strategic tool to help your team decide where to put its development efforts. Since Impact Mapping is about deciding what work to consider doing, with past clients I have used it prior to putting any effort into creating the Product Backlog, and I would even consider doing it before Story or Journey Mapping – both of which involve exploring the journey of a user through the system the team is building.

Summary

Impact Mapping ensures that when we discuss a piece of work, it always remains in context of our overall Goal, and it can also help us see that there are many paths to it.

Never implement the whole map – instead, run experiments to see which path will get you to the Goal the soonest/with the least amount of effort.

Finally, you can use Impact Maps for more than just product development work; they also help when undertaking organizational change.

Impact Mapping – Glossary and Additional References

Want to learn more about Impact Mapping and other strategies to help your team identify the best way to get more bang for the buck? Our Certified Scrum Product Owner training uses real-life examples and hands-on practice to help you and your team understand how to create ideal customer and organization outcomes, not just produce widgets and complete tasks.

Image attributes: Agile Pain Relief Consulting, except Figure 1: Creative Commons 4.0 as per: https://www.impactmapping.org/drawing.html. (Updated November 2023)

Footnotes

-

The original book used “Who” for Actor; How for “Impact” and “What” for Deliverable – I find the newer versions far more clear ↩

-

From Chris Matts https://theitriskmanager.wordpress.com/ ↩

-

Gojko offers this list as a simplified version of the advice from Competitive Engineering by Tom Gilb ↩

-

Innovation Games by Luke Hohmann https://www.innovationgames.com/resources/innovation-games-book/ ↩

-

Gamestorming by Dave Gray https://gamestorming.com/ ↩

-

From the Business Value Game by Andrea Tomasini https://www.agile42.com/en/business-value-game/ ↩

-

Kano Model http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kano_model ↩

-

“Splitting user stories — the hamburger method” by Gojko Adzic https://gojko.net/2012/01/23/splitting-user-stories-the-hamburger-method/ ↩

Mark Levison

Mark Levison has been helping Scrum teams and organizations with Agile, Scrum and Kanban style approaches since 2001. From certified scrum master training to custom Agile courses, he has helped well over 8,000 individuals, earning him respect and top rated reviews as one of the pioneers within the industry, as well as a raft of certifications from the ScrumAlliance. Mark has been a speaker at various Agile Conferences for more than 20 years, and is a published Scrum author with eBooks as well as articles on InfoQ.com, ScrumAlliance.org and AgileAlliance.org.