Mismeasurement Mess - IRCC Leads the Way

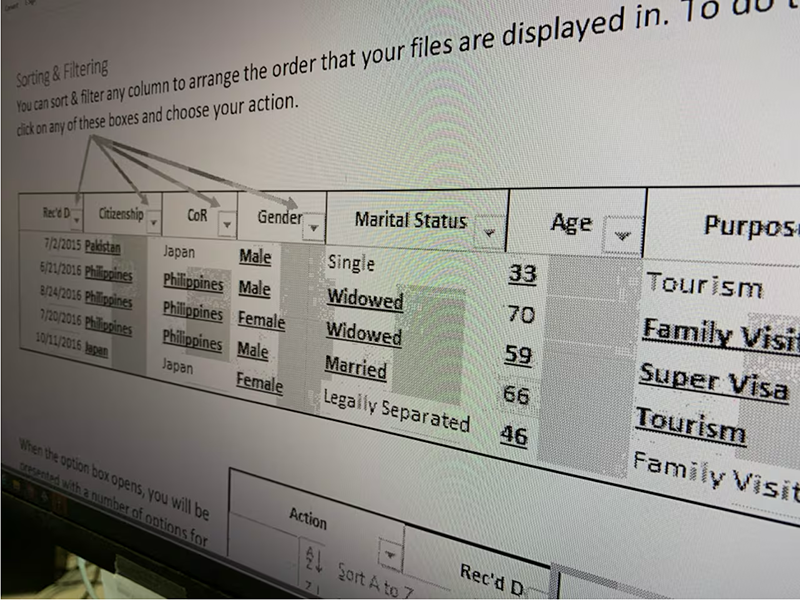

Immigration and Refugees Citizenship Canada (IRCC) is measuring how long it takes immigration officers to process visa and immigration applications. Should be a win, right? Not so fast. Imagine working with an immigration lawyer to prepare an application of several hundred pages in length, then the decision is made in less than a minute, with the IRCC officer looking at several files at once. How would you feel if you were the applicant?1

We have a backlog of visa and immigration applications; the problem is real. Pretending that an immigration officer can review multiple applications simultaneously defies an understanding of how human brains work. The system provides a point and click Approve or Deny system with 3-4 applications displayed at the same time. Some of these applications are over 200 pages in length, so some applicants are getting denials with responses like:

- Missing birth certificate - yet it was attached

- Not enough income or cash for their stay - yet the application proves that they have more than enough

- …

One former immigration officer explains that in recent years, the only thing that matters is getting the file processed and the backlog cleared - a local optimization.

As Canadians, we want our government to treat people fairly, so it feels wrong to hear about visa applications being denied for the wrong reasons. Fairness aside, this approach clogs the system with appeals. So instead of clearing the backlog faster, we’ve created a new backlog. The local optimization created a systematic problem.

This has been seen before in places like call centres when we measure the speed at which individual agents handle calls. The agent learns that if it is a simple problem, they can help you quickly. If the problem turns out to be complex? Find a way to lose the call (hang up 😉️) and the complex customer becomes someone else’s problem.

There are three key problems in the IRCC example:

- Only one measure

- The wrong thing appears to be measured

- The measure became a target and is incentivized (commonly known as Goodhart’s Law)

When we measure systems, we’re better off finding measures that balance each other. For example, in a software development team I want something to measure throughput (how long it takes items to get finished) but also quality and team health. (Ideally, I would also measure value delivered to the customer, however, after 15 years of looking, I still haven’t found this measure.)

If too much focus is put on throughput, the quality and health metrics will suffer.

When building measurement systems:

- Look for balance - You wouldn’t measure only throughput without considering quality and team health. Avoid single measures.

- Run the “What if everyone maximizes this?” thought experiment - If we measure only speed, what will happen? Probably more defects and burnout and, in IRCC’s case, more appeals.

- Ask “How will people game the measure?” - Measure story points and we will get lots of story points. Double your estimates, no testing. How could it go wrong?

- Measure the whole system, not just a single station - In Kanban, we learn to study the flow of work through the whole system, not just one station.

Good metrics provide a diagnostic tool; they’re not a target. When I see “Cycle Time” outliers in a team, I use it as a hint to investigate what is going on.

In IRCC’s case, the only measure appears to be the number of applications processed. Worse, it seems managers are incentivized to maximize this number. So officers are doing exactly what they’re measured on.

With a few days studying their system to understand what we want to measure to create healthy outcomes, IRCC could then use that to improve their system, clear the backlog mess and treat applicants fairly and humanely.

Agile Pain Relief Blog Entries

Image attribution: CBC (Sept 2025)

Footnotes

-

Immigration lawyers concerned IRCC’s use of processing technology leading to unfair visa refusals - Shaina Luck https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/immigration-canada-ircc-technology-1.7632130 ↩

Mark Levison

Mark Levison has been helping Scrum teams and organizations with Agile, Scrum and Kanban style approaches since 2001. From certified scrum master training to custom Agile courses, he has helped well over 8,000 individuals, earning him respect and top rated reviews as one of the pioneers within the industry, as well as a raft of certifications from the ScrumAlliance. Mark has been a speaker at various Agile Conferences for more than 20 years, and is a published Scrum author with eBooks as well as articles on InfoQ.com, ScrumAlliance.org and AgileAlliance.org.