GenAI Code Quality – The Fundamental Flaws and How Bluffing Makes It Worse

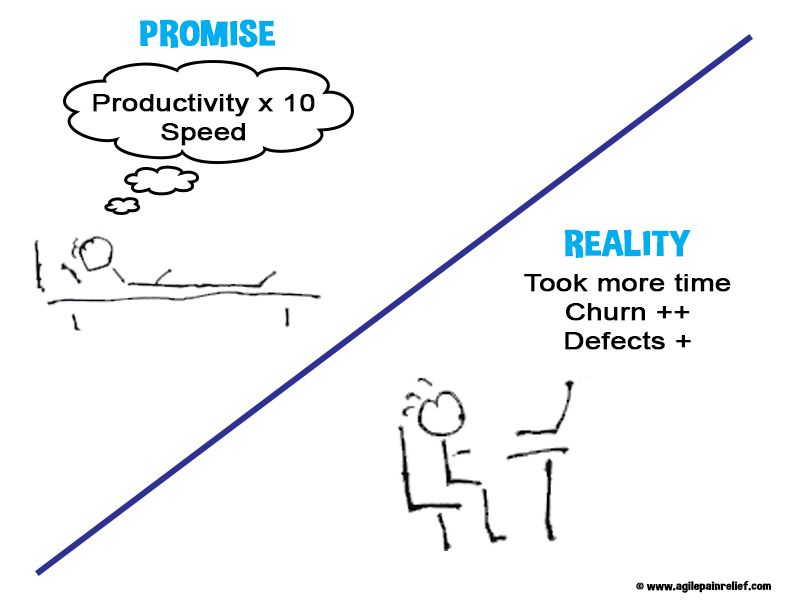

AI-generated code has 1.7x more issues, the GenAI code quality gap is turning into a chasm. That’s not a random number, that’s from a CodeRabbit research report1. You’ve probably already seen the problem yourself. AI-generated, quick to write, harder to read and maintain. Why? Researchers from the GENIUS project2 put it plainly: training focuses on pass/fail — does the code compile, does it pass the tests? There’s no reward for writing code that’s easy to maintain.

Previously, I demonstrated that LLMs are increasing defect density in their generated code and are a source of increased production defects, security vulnerabilities, and other issues.

Defect Density: The number of defects per unit of code, usually per 1,000 lines of code. Why is this important? Because LLM-generated code has more defects than human-written code. The CodeRabbit report takes further and shows 30–41% more tech debt, and 39% more cognitive complexity.1

Cognitive Complexity: is a measure created by SonarQube that assesses how difficult it is to understand a piece of code.

Some teams think TDD is the fix. They’re solving the wrong problem. Others suggest we can code review our way out of this. That’s not going to work either.

These problems are structural. To understand them, you need to look at how the models are trained and that plumbing hasn’t changed since 2023. Model refinements since 2024/2025 haven’t changed the fundamentals of these models, which are built. If we want to avoid the pitfalls inherent in these models, we need to understand how they are trained and the types of mistakes they make.

The Four Core Flaws of GenAI Code

Training

- Pass/fail is all that matters. Training and evaluation systems reward code that compiles and passes functional tests, which creates a “test-taking” mode that penalizes acknowledging uncertainty. There is no reward for nuance models that learn to “bluff” with plausible but overconfident best guesses because 0-1 grading schemes incentivize guessing over admitting a lack of knowledge.3

- Benchmarks don’t generalize. A model that scores well on HumanEval or SWE-Bench doesn’t necessarily write good code in your codebase. Worse, some of those benchmarks have contaminated the training data, so even the scores are suspect.3

- Trained on the average of the Internet. These models learned from the internet’s code — the same code we used to joke about never copying from StackOverflow. Now we do it at scale and call it productivity.4 5

- No understanding of design. The model has no coherent grasp of architecture, design patterns, or programming paradigms. It doesn’t know OO from functional — it just predicts the next token.6

- Silent failures. Newer models aren’t always an improvement. Jamie Twiss reports in IEEE Spectrum7 a pattern with recent models that were more likely to silently fail when asked to fix a simple Python error, producing code that looks correct but quietly removes safety checks or fakes output to avoid crashing.

Maintainability

- Duplication and Extensive edits everywhere. This occurs because the model doesn’t know where to make changes. That churn destabilizes otherwise-stable code, and bug fixing turns into whack-a-mole.6

- Your conventions don’t matter. The models don’t follow the patterns in your codebase, making the output harder to understand.6 8

- Correct but brittle. The reward functions used to fine-tune the models optimize for “does it work,” not for principles such as DRY or CUPID. You get code that passes today and breaks the moment something changes.6

OX Security likens this to an “army of junior developers”, fast and functional, but lacking architectural judgment.9 They also found the models are excellent at generating test coverage without writing meaningful tests.

Security and Predictability

- Security vulnerabilities built in. The models have learned from the average code on the internet. Security flaws and all. So it’s no surprise, they’re excellent at replicating them. Good security is designed in from the start, not bolted on after the fact.10

- Popular choice over good. Given the choice, models default to whatever’s most popular: Python over Rust, React over Svelte, the big library over the specialized one. Popularity isn’t a design decision, but the model treats it like one.11

In addition, Veracode’s 2025 GenAI Code Security Report12 demonstrates that models can’t simply be trained on better security principles, because security requires understanding context. Is this piece of data under system control or was it entered by an end user? Is this piece of code on an internal system or exposed to the internet?

Your Code base

- Blind to your domain. The model doesn’t know your business, your users, or the problem you’re solving. It generates code without context for why that code needs to exist.13 8

- Scattered sources, incomplete picture. Your code lives in one place, your user stories/PBIs in another, your documentation somewhere else. Even if the model has access to all of it, the connections between a specific user story and the code that implements it are hard to see. So the model never sees the full picture.8 13

- Context windows have a middle problem. Even large context windows don’t solve this. Models tend to lose focus on the middle, paying attention to the start and end while forgetting the parts that matter.13 8 Strangely, the model suffers from similar cognitive biases as we humans3, see: Primacy14 and Recency Effects15.

Some of this we try to retrofit by adding more rules or context via Claude.md or Claude/Agent skills. I.E. Explicitly telling the model about the DRY principle or giving it an outline of your project structure. However, that only goes so far. The more we stuff into the Claude.md file, the less room there is in the models context window for the code itself.

We can’t wait for the labs to make this better; it will require a fundamental shift in what they focus on and how they train the models. Since that isn’t happening, we need to find a way to deal with this ourselves. If someone wants to fund a better approach, I’m available. Until then, we deal with what we’ve got.

What gets us out of this mess? TDD? Code Reviews?

Wow, that is a lot of issues. How do we deal with this? Contrary to a few comments, we can’t code review our way out of this mess. That’s putting the burden on humans to tidy up the mess that the AI created. Code reviews are so bad that they will get a blog post of their own. (See also: The Real Cost of AI-Generated Code and Using GenAI to Code? Not So Fast.) And don’t get me started on the idea of LLM reviewing another LLM’s output, again, that’s a misunderstanding of what these tools are good for.

So what about TDD? It helps, but it’s solving the wrong problem. TDD helps developers clarify what they’re solving before how, by expressing understanding as small, concrete, failing tests. It’s a thinking tool, not a testing tool. That makes it valuable for AI-generated code: it forces you to understand the problem before accepting the solution. But TDD operates at the code level. It can’t tell you whether the feature itself is waste. I haven’t seen any evidence that TDD, combined with GenAI, will reduce Technical Debt, duplication, or cognitive complexity.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The models won’t fix themselves, and the labs aren’t prioritizing what matters: well-designed architecture, maintainability, security in context, and respect for your codebase. Some of it can’t be designed in the models no matter how we try.

The Shift Left movement has always had the right idea: Continuous Discovery, Lean Startup Experiments, Lean UX, and real BDD (i.e., collaboration on examples). The job is to build great products, not blindly shovel more defect-laden code into production.

When it comes to the code itself, give the models smaller, more focused tasks. Start with a small set of acceptance criteria for a single feature and work from there.

Instead of trying to do a better job of building quality into code faster. Why don’t we work on making sure we know what the right product is first? What are you doing to survive this mess? I genuinely want to know.

LLM Usage Note

Parallel.AI for research, NotebookLLM to ground-check claims against source material, and Gemini via Obsidian Copilot for writing critique. Claude Code helps turn the markdown text into mdx file for a blog post.

Footnotes

-

CodeRabbit, “State of the AI vs. Human Code Generation Report,” external:https://www.coderabbit.ai/whitepapers/state-of-AI-vs-human-code-generation-report ↩ ↩2

-

Robin Gröpler et al., “The Future of Generative AI in Software Engineering: A Vision from Industry and Academia in the European GENIUS Project,” external:https://arxiv.org/html/2511.01348v2 ↩

-

Adam Tauman Kalai, Ofir Nachum, Santosh S. Vempala, and Edwin Zhang, “Why Language Models Hallucinate,” external:https://arxiv.org/pdf/2509.04664.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Kaushik Bar, “AI for Code Synthesis: Can LLMs Generate Secure Code?,” external:https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5157837 ↩

-

Shuai Wang, Liang Ding, Li Shen, Yong Luo, Bo Du, and Dacheng Tao, “OOP: Object-Oriented Programming Evaluation Benchmark for Large Language Models,” external:https://arxiv.org/pdf/2401.06628.pdf ↩

-

Mootez Saad, José Antonio Hernández López, Boqi Chen, Neil Ernst, Dániel Varró, and Tushar Sharma, “SENAI: Towards Software Engineering Native Generative Artificial Intelligence,” external:https://arxiv.org/pdf/2503.15282.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Jamie Twiss, “AI Coding Degrades: Silent Failures Emerge,” IEEE Spectrum, January 2026, external:https://spectrum.ieee.org/ai-coding-degrades ↩

-

Jiessie Tie, Bingsheng Yao, Tianshi Li, Syed Ishtiaque Ahmed, Dakuo Wang, and Shurui Zhou, “LLMs are Imperfect, Then What? An Empirical Study on LLM Failures in Software Engineering,” external:https://arxiv.org/pdf/2411.09916.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

OX Security, “Army of Juniors: The AI Code Security Crisis,” October 2025, external:https://www.ox.security/resource-category/whitepapers-and-reports/army-of-juniors/ ↩

-

Manish Bhatt, Sahana Chennabasappa, Cyrus Nikolaidis et al., “Purple Llama CyberSecEval: A Secure Coding Benchmark for Language Models,” external:https://arxiv.org/pdf/2312.04724.pdf ↩

-

Lukas Twist, Jie M. Zhang, Mark Harman, Don Syme, Joost Noppen, Helen Yannakoudakis, and Detlef Nauck, “A Study of LLMs’ Preferences for Libraries and Programming Languages,” external:https://arxiv.org/pdf/2503.17181.pdf ↩

-

Veracode, “2025 GenAI Code Security Report,” July 2025, external:https://www.veracode.com/resources/analyst-reports/2025-genai-code-security-report/ ↩

-

Cuiyun Gao, Xing Hu, Shan Gao, Xin Xia, and Zhi Jin, “The Current Challenges of Software Engineering in the Era of Large Language Models,” external:https://arxiv.org/pdf/2412.14554.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

“Primacy Effect,” The Decision Lab, external:https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/primacy-effect ↩

-

“Recency Effect,” The Decision Lab, external:https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/recency-effect ↩

Mark Levison

Mark Levison has been helping Scrum teams and organizations with Agile, Scrum and Kanban style approaches since 2001. From certified scrum master training to custom Agile courses, he has helped well over 8,000 individuals, earning him respect and top rated reviews as one of the pioneers within the industry, as well as a raft of certifications from the ScrumAlliance. Mark has been a speaker at various Agile Conferences for more than 20 years, and is a published Scrum author with eBooks as well as articles on InfoQ.com, ScrumAlliance.org and AgileAlliance.org.